(United States GDP plotted against median household income from 1953 to present. Until about 1980, growth in the economy correlated to increases in household wealth. But from 1980 onwards as digital technology has transformed the economy, household income has remained flat despite continuing economic growth. From “The Second Machine Age“, by MIT economists Andy McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, summarised in this article.)

(Or, why technology created the economy that helped Donald Trump and Brexit to win, and why we have to fix it.)

The world has not just been thrown into crisis because the UK voted in June to leave the European Union, and because the USA has just elected a President whose campaign rhetoric promised to tear up the rulebook of international behaviour (that’s putting it politely; many have accused him of much worse) – including pulling out of the global climate accord that many believe is the bare minimum to save us from a global catastrophe.

Those two choices (neither of which I support, as you might have guessed) were made by people who feel that a crisis has been building for years or even decades, and that the traditional leaders of our political, media and economic institutions have either been ignoring it or, worse, are refusing to address it due to vested interests in the status quo.

That crisis – which is one of worklessness, disenfranchisement and inequality for an increasingly significant proportion of the world’s population – is real; and is evident in figures everywhere:

… and so on.

Brexit and Donald Trump are the wrong solutions to the wrong problems

Of course, leaving the EU won’t solve this crisis for the UK.

Take the supposed need to limit immigration, for example, one of the main reasons people in the UK voted to leave the EU.

The truth is that the UK needs migrants. Firstly, with no immigration, the UK’s birth rate would be much lower than that needed to maintain our current level of population. That means less young people working and paying taxes and more older people relying on state pensions and services. We wouldn’t be able to afford the public services we rely on.

Secondly, the people most likely to start new businesses that grow rapidly and create new jobs aren’t rich people who are offered tax cuts, they’re immigrants and their children. And of course, what will any country in the world, let alone the EU, demand in return for an open trade deal with the UK? Freedom of immigration.

So Brexit won’t fix this crisis, and whilst Donald Trump is showing some signs of moderating the extreme statements he made in his election campaign (like both the “Leave” and “Remain” sides of the abysmal UK Referendum campaign, he knew he was using populist nonsense to win votes, but wasn’t at all bothered by the dishonesty of it), neither will he.

[Update 29/01/17: I take it back: President Trump isn’t moderating his behaviour at all. What a disgrace.]

Whatever his claims to the contrary, Donald Trump’s tax plan will benefit the richest the most. Like most Republican politicians, he promotes policies that are criticised as “trickle-down” economics, in which wealth for all comes from providing tax cuts to rich people and large corporations so they can invest to create jobs.

But this approach does not stand up to scrutiny: history shows that – particularly in times of economic change – jobs and growth for all require leadership, action and investment from public institutions – in other words they depend on the sensible use of taxation to redistribute the benefits of growth.

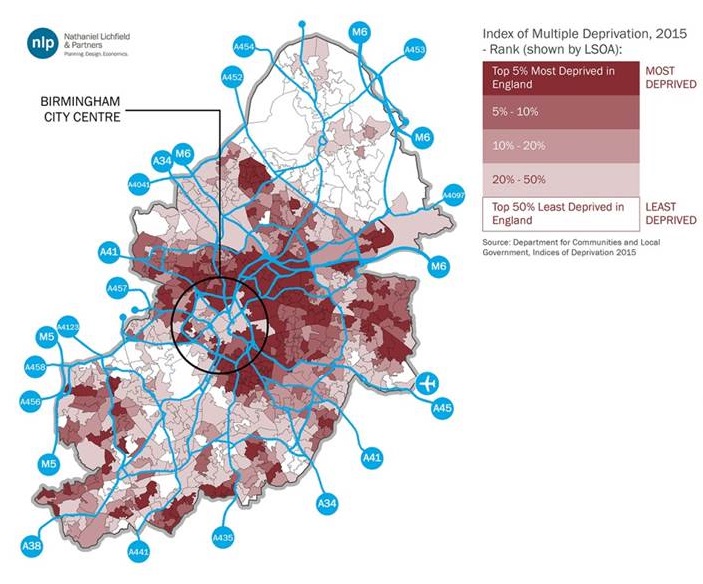

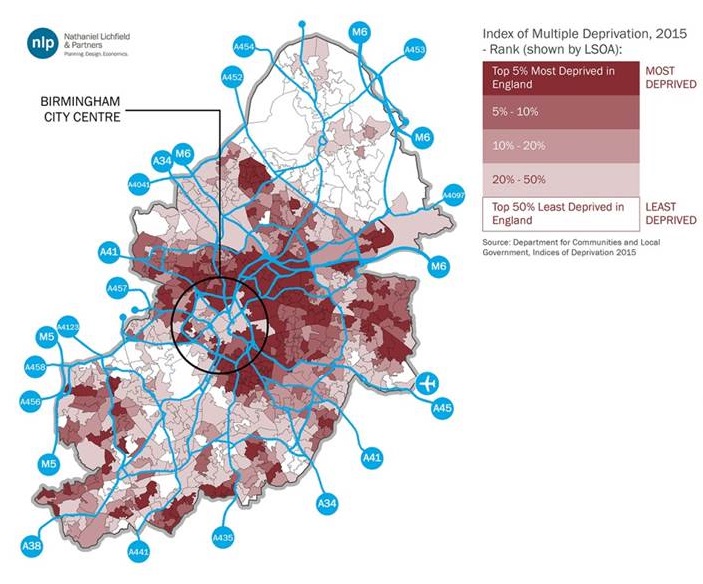

(Areas of relative wealth and deprivation in Birmingham as measured by the Indices of Multiple Deprivation. Birmingham, like many of the UK’s Core Cities, has a ring of persistently deprived areas immediately outside the city centre, co-located with the highest concentration of transport infrastructure allowing traffic to flow in and out of the centre)

Similarly, scrapping America’s role in the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal is unlikely to bring back manufacturing jobs to the US economy at anything like the scale that some of those who voted for Donald Trump hope, and that he’s given the impression it will.

In fact, manufacturing jobs are already rising in the US as the need for agility in production in response to local market conditions outweighs the narrowing difference in manufacturing cost as the salaries of China’s workers have grown along with its economy.

However, the real challenge is that the skills required to secure and perform those jobs have changed: factory workers need increasingly technical skills to manage the robotic machinery that now performs most of the work.

Likewise, jobs in the US coal industry won’t return by changing the way the US trades with foreign countries. The American coal mined in some areas of the country has become an uncompetitive fuel compared to the American shale gas that is made accessible in other areas by the new technology of “fracking”. (I’m not in favour of fracking; I’d prefer we concentrate our resources developing genuinely low-carbon, renewable energy sources. My point is that Donald Trump’s policies won’t address the job dislocation it has caused).

So, if the UK’s choice to leave the EU and the USA’s choice to elect Donald Trump represent the wrong solutions to the wrong problems, what are the underlying problems that are creating a crisis? And how do we fix them?

The crisis begins in places that don’t work

When veteran BBC journalist John Humphreys travelled the UK to meet communities which have experienced a high degree of immigration, he found that immigration itself isn’t a problem. Rather, the rise in population caused by immigration becomes a problem when it’s not accompanied by investment in local infrastructure, services and business support. Immigrants are the same as people everywhere: they want to work; they start businesses (and in fact, they’re more likely to do that well than those of us who live and work in the country where we’re born); and they do all the other things that make communities thrive.

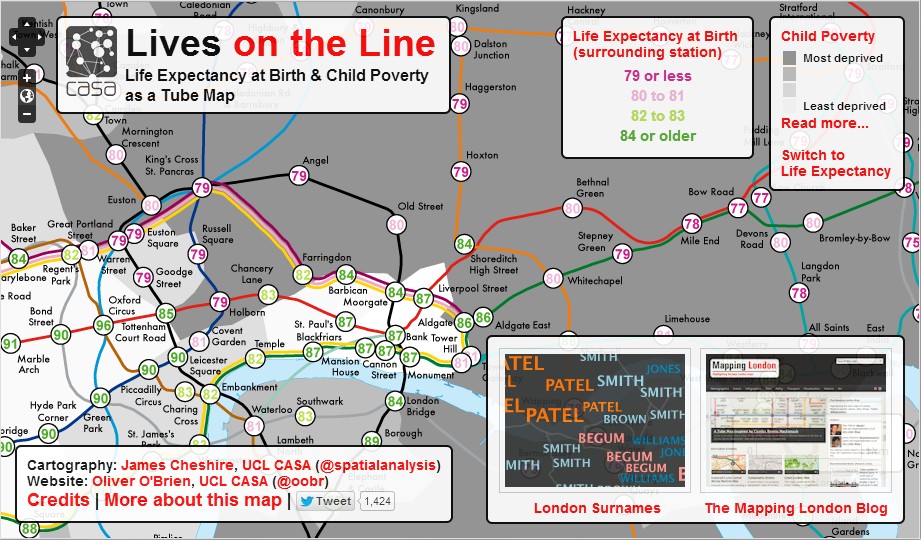

But the degree to which people – whether they’re immigrants or not – are successful doing so depends on the quality of their local environment, services and economy. And the reality is that there are stark, place-based differences in the opportunity people are given to live a good life.

In UK cities, life expectancy between the poorest and richest parts of the same city varies by up to 28 years. Areas of low life expectancy typically suffer from “multiple deprivation“: poor health, low levels of employment, low income, high dependency on benefits, poor education, poor access to services … and so on. These issues tend to affect the same areas for decade after decade, and they occur in part because of the effects of the physical urban infrastructure around them.

The failure to invest in local services and infrastructure to accommodate influxes of migrants isn’t the EU’s fault; it is caused by the failure of the UK national government to devolve spending power to the local authorities that understand local needs – local authorities in the UK control only 17% of local spending, as opposed to 55% on average across OECD countries.

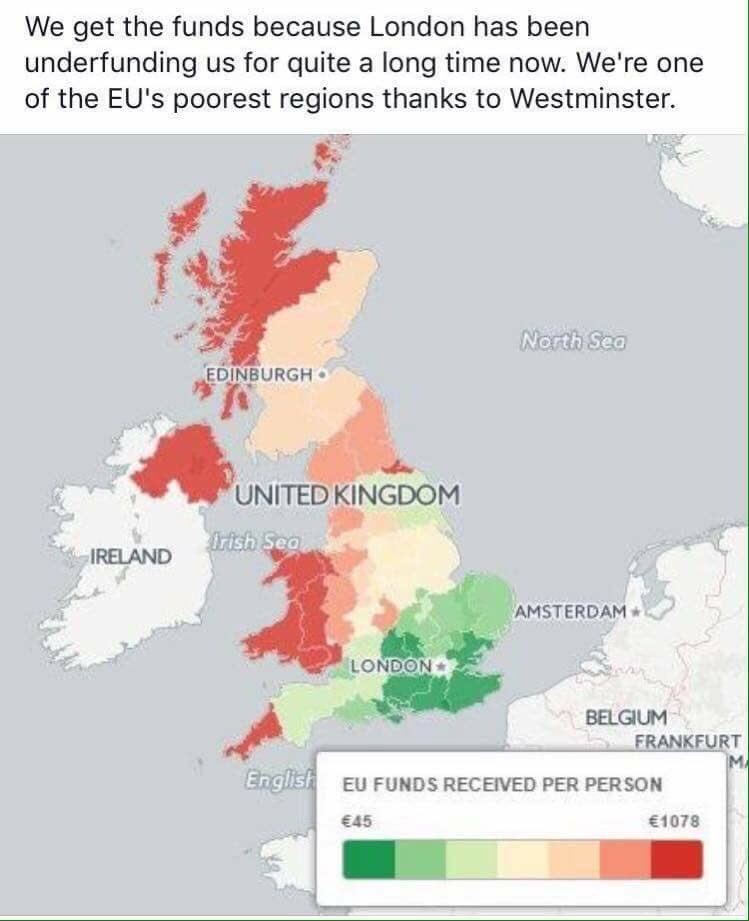

Ironically, one of the crucial things the EU does (or did) with the UK’s £350 million per week contribution to its budget, a large share of which is paid for by taxes from London’s dominant share of the UK economy, is to give it back to support local infrastructure and projects which create jobs and improve communities. If the Remain campaign had done a better job of explaining the extent of this support, rather than trumpeting overblown scare stories about the national, London-centric economy from which many people feel they don’t benefit anyway, some of the regions most dependent on EU investment might not have voted to Leave.

Technology is exacerbating inequality

We should certainly try to improve urban infrastructure and services; and the “Smart City” movement argues for using digital technology to do so.

But ultimately, infrastructure and services simply support activity that is generated by the economy and by social activity, and the fundamental shift taking place today is not a technological shift that makes existing business models, services or infrastructure more effective. It is the transformation of economic and social interactions by new “platform” business models that exploit online transaction networks that couldn’t exist at all without the technologies we’ve become familiar with over the last decade.

Well known examples include:

- Apple iTunes, exchanging music between producers and consumers

- YouTube, exchanging video content between producers and consumers

- Facebook, an online environment for social activity that has also become a platform for content, games, news, business and community activity

- AirBnB – an online marketplace for peer-to-peer arrangement of accomodation

- Über – an online marketplace for peer-to-peer arrangement of transport

… and so on. MIT economist Marshall Van Alstyne’s work shows that platform businesses are increasingly the most valuable and fastest growing in the world, across many sectors.

The last two examples in that list – AirBnB and Über – are particularly good examples of online marketplaces that create transactions that take place face-to-face in the real world; these business models are not purely digital as YouTube, for example, arguably is.

But whilst these new, technology-enabled business models can be extraordinarily successful – Airbnb has been valued at $30 billion only 8 years after it was founded, and Über recently secured investments that, 7 years after it was founded, valued the company at over $60 billion – many economists and social scientists believe that the impact of these new technology-enabled business models is contributing to increasing inequality and social disruption.

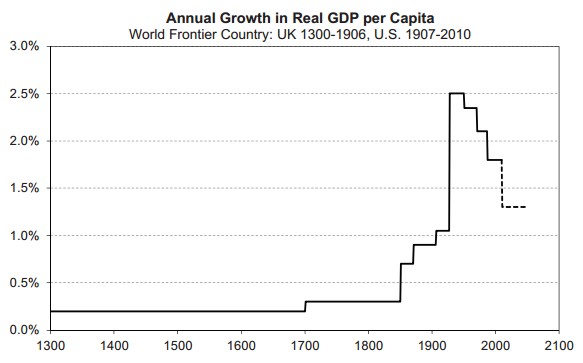

As Andy McAfee and Erik Bryjolfsson have explained in theory, and as a recent JP Morgan survey has demonstrated in fact (see graph and text in box below), as traditional businesses that provide permanent employment are replaced by online marketplaces that enable the exchange of casual labour and self-employed work, the share of economic growth that is captured by the owners of capital platforms – the owners and shareholders in companies like Amazon, Facebook and Über – is rising, and the share of economic growth that is distributed to people who provide labour – people who are paid for the work they do; by far the majority of us – is falling.

The impact of technology on the financial services sector is having a similar effect. Technology enables the industry to profit from the construction of increasingly complex derivative products that speculate on sub-second fluctuations in the value of stocks and other tradeable commodities, rather than by making investments in business growth. The effect again is to concentrate the wealth the industry creates into profits for a small number of rich investors rather than distributing it in businesses that more widely provide jobs and pay salaries.

Finally, this is also ultimately the reason why the various shifting forces affecting employment in traditional manufacturing industries – off-shoring, automation, re-shoring etc. – have not resulted in a belief that manufacturing industries are providing widespread opportunities for high quality employment and careers to the people and communities who enjoyed them in the past. Even whilst manufacturing activity grows in many developed countries, jobs in those industries require increasingly technical skills, at the same time that, once again, the majority of the profits are captured by a minority of shareholders rather than distributed to the workforce.

That is why inequality is rising across the world; and that is the ultimate cause of the sense of unfairness that led to the choice of people in the UK to leave the EU, and people in the USA to elect Donald Trump as their President.

I do not blame the companies at the heart of these developments for causing inequality – I do not believe that is their aim, and many of their leaders believe passionately that they are a force for good.

But the evidence is clear that their cumulative impact is to create a world that is becoming damagingly unequal, and the reason is straightforward. Our market economies reward businesses that maximise profit and shareholder return; and there is simply no direct link from those basic corporate responsibilities to wider social, economic and environmental outcomes.

There are certainly indirect links – successful businesses need customers with money to spend, and there are more of those when more people have jobs that pay good wages, for example. But technology is increasingly enabling phenomenally successful new business models that depend much less on those indirect links to work.

We’re about to make things worse

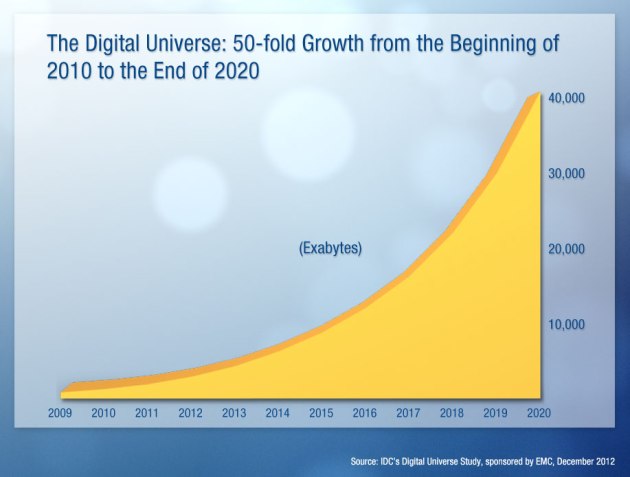

Finally, as has been frequently highlighted in the media recently, new developments in technology are likely to further exacerbate the challenges of worklessness and inequality.

After a few decades in which scientific and technology progress in Artifical Intelligence (AI) made relatively little impact on the wider world, in the last few years the exponential growth of data and the computer processing power to manipulate it have led to some striking accomplishments by “machine learning”, a particular type of AI technology.

Whilst Machine Learning works in a very different way to our own intelligence, and whilst the Artificial Intelligence experts I’ve spoken to believe that any technological equivalent to human intelligence is between 20 and 100 years away (if it ever comes at all), one thing that is obvious is that Machine Learning technologies have already started to automate jobs that previously required human knowledge. Some studies predict that nearly half of all jobs – including those in highly-skilled, highly-paid occupations such as medicine, the law and journalism- could be replaced over the next few decades.

(Population changes in Blackburn, Burnley and Preston from 1901-2001. In the early part of the century, all three cities grew, supported by successful manufacturing economies. But in the latter half, only Preston continued to grow as it transitioned successfully to a service economy. If cities do not adapt to changes in the economy driven by technology, history shows that they fail. From “Cities Outlook 1901” by Centre for Cities)

Über is perhaps the clearest embodiment of these trends combined. Whilst several cities and countries have compelled the company to treat their drivers as employees and offer improved terms and conditions, their strategy is unapologetically to replace their drivers with autonomous vehicles anyway.

I’m personally convinced that what we’re experiencing through these changes – and what we’ve possibly been experiencing for 50 years or more – is properly understood to be an Information Revolution that will reshape our world every bit as significantly as the Industrial Revolution.

And history shows us we should take the economic and social consequences of that very seriously indeed.

In the last Century as automated equipment replaced factory workers, many cities in the UK such as Sunderland, Birmingham and Bradford, saw severe job losses, economic depression and social challenges as they failed to adapt from a manufacturing economy to new industries based on knowledge-working.

In this Century many knowledge-worker jobs will be automated too, and unless we knowingly and successfully manage this huge transition into an economy based on jobs we can’t yet predict, the social and economic consequences – the crisis that has already begun – will be just as bad, or perhaps even worse.

So if the problem is the lack of opportunity, what’s the answer?

If trickle-down economics doesn’t work, top-down public sector schemes of improvement won’t work either – they’ve been tried again and again without much improvement to those persistently, multiply-deprived areas:

“For three generations governments the world over have tried to order and control the evolution of cities through rigid, top-down action. They have failed. Masterplans lie unfulfilled, housing standards have declined, the environment is under threat and the urban poor have become poorer. Our cities are straining under the pressure of rapid population growth, rising inequality, inadequate infrastructure, and failing systems of urban planning, design and development.”

– from “The Radical Incrementalist” by Kelvin Campbell, summarised here.

One of the most forward-looking UK local authority Chief Executives said to me recently that the problem isn’t that a culture of dependency on benefits exists in deprived communities; it’s that a culture of doing things for and to people, rather than finding ways to support them succeeding for themselves, permeates local government.

This subset of findings from Sir Bob Kerslake’s report on Birmingham City Council reflects similar concerns:

- “The council, members and officers, have too often failed to tackle difficult issues. They need to be more open about what the most important issues are and focus on addressing them;

- Partnership working needs fixing. While there are some good partnerships, particularly operationally, many external partners feel the culture is dominant and over-controlling and that the council is complex, impenetrable and too narrowly focused on its own agenda;

- The council needs to engage across the whole city, including the outer areas, and all the communities within it;

- Regeneration must take place beyond the physical transformation of the city centre. There is a particularly urgent challenge in central and east Birmingham.”

One solution that’s being proposed to the challenges of inequality and the displacement of jobs by automation is the “Universal Basic Income” – an unconditional payment made by government to every citizen, regardless of income and employment status. The idea is that such a payment ensures a good enough standard of living for everyone, even if many people lose employment or see their salaries fall; or chose to work in less financially rewarding occupations that have strong social value – caring for others, for example. Several countries, including Finland, Canada and the Netherlands have already begun pilots of this idea.

I think it’s a terrible mistake for two reasons.

Firstly, the proposed level of income – about $1500 per month – isn’t at all sufficient to address the vast levels of inequality that our economy has created. Whilst it might allow a majority of people to live a basically comfortable life, why should we accept that a small elite should exist at such a phenomenally different level of technology-enabled wealth as to be reminiscent of a science fiction dystopia?

Andy McAfee and Erik Brynjofflsson best expressed the second problem with a Universal Basic Income by quoting Voltaire in “The Second Machine Age“:

“Work keeps at bay three great evils: boredom, vice, and need.”

A Universal Basic Income might address “need”, to a degree, but it will do nothing to address boredom and vice. Most people want to work because they want to be useful, they want their lives to make a difference and they want to feel fulfilled – this is the “self-actualisation” at the apex of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Surely enabling everyone to reach that condition should be our aspiration for society, not a subsidy that addresses only basic needs?

Our answer to these challenges should be an economy that properly rewards the application of effort, talent and courage to achieving the objectives that matter to us most; not one that rewards the amoral maximisation of profits for the owners of capital assets accompanied by a gesture of redistribution that’s just enough to prevent civil unrest.

(Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs”)

Three questions that reveal the solution

There are three questions that I think define the way to answer these challenges in a way that neither the public, private nor third sectors have yet done.

The first is the question at the heart of the idea of a Smart City.

There are a million different definitions of a “Smart City”, but most of them are variations on the theme of “using digital technology to make cities better”. The most challenging part of that idea is not to do with how digital technology works, nor how it can be used in city systems; it is to do with how we pay for investments in technology to achieve outcomes that are social, economic and environmental – i.e. that don’t directly generate a financial return, which is usually why money is invested.

Of course, there are investment vehicles that translate achievement against social, economic or environmental objectives into a financial return – Social Impact Bonds and Climate Bonds, for example.

Using such vehicles to support the most interesting Smart City ideas can be challenging, however, due to the level of uncertainty in the outcomes that will be achieved. Many Smart City ideas provide people with information or services that allow them to make choices about the energy they use; how and when they travel; and the products and services they buy. The theory is that when given the option to improve their social, economic and environmental impact, people will chose to do so. But that’s only the theory; the extent to which people actually change their behaviour is notoriously unpredictable. That makes it very difficult to create an investment vehicle with a predictable level of return.

So the first key question that should be answered by any solution to the current crisis is:

- QUESTION 1: How can we manage the risk of investing in technology to achieve uncertain social, economic or environmental aims such as improving educational attainment or social mobility in our most deprived areas?

The international Smart City community (of which I am a part) has so far utterly failed to answer that question. In the 20 years that the idea has been around, it simply hasn’t made a noticeable difference to economic opportunity, social mobility or resilience – if it had, I wouldn’t be writing this article about a crisis. Earlier this year, I described the examples of Smart City initiatives around the world that are finally starting to make an impact, and below I’ll describe some actions we can take to replicate them and drive them forward at scale.

The second question is inspired by the work of the architect and town planner Kelvin Campbell, whose “Smart Urbanism” is challenging the decades of orthodox thinking that has failed to improve those most deprived areas of our cities:

“The solution lies in mobilising peoples’ latent creativity by harnessing the collective power of many small ideas and actions. This happens whenever people take control over the places they live in, adapting them to their needs and creating environments that are capable of adapting to future change. When many people do this, it adds up to a fundamental shift. This is what we call making Massive Small change.”

– from “The Radical Incrementalist” by Kelvin Campbell, summarised here.

Kelvin’s concept of “Massive Small change” forms the second key question that defines the solution to our crisis:

- QUESTION 2: What are the characteristics of urban environments and policy that give rise to massive amounts of small-scale innovation?

That’s one of the most thought-provoking and insightful questions I can think of. “Small-scale” innovation is what everybody does, every day, as we try to get by in life: fixing a leaky tap, helping our daughter with her maths homework, closing that next deal at work, losing another kilogram towards our weight target, becoming a trustee of a local charity … and so on.

For some people, what begin as small-scale innovations eventually amount to tremendously successful lives and careers. Mark Zuckerberg learned how to code, developed an online platform for friends to stay in touch with each other, and became the 6th richest man on the planet, worth approximately $40 billion. On the other hand, 15 million people around the world, including a vast number of children, show their resourcefulness by searching refuse dumps for re-usable objects.

Recent research on the platform economy by the not-for-profit PEW Research Centre confirms these vast gaps in opportunity; and most concerningly identifies clear biases based on race, class, wealth and gender.

The problem with small-scale innovation doesn’t lie in making it happen – it happens all the time. The problem lies in enabling it to have a bigger impact for those in the most challenging circumstances. Kelvin’s work has found ways to do that in the built environment; how do we translate those ideas into the digital economy?

The final question is more subtle:

- QUESTION 3: How do we ensure that massive amounts of small-scale innovation create collective societal benefits, rather than lots of individual successes?

One way to explain what I mean by the difference between widespread individual success and societal success is in terms of resilience. Over the next 35 years, about 2 billion more people worldwide will acquire the level of wealth associated with the middle classes of developed economies. As a consequence, they are likely to dramatically increase their consumption of resources – eating more meat and less vegetables; buying cars; using more energy. Given that we are already consuming our planet’s resources at an unsustainable rate, such an increase in consumption could great an enormous global problem. So our concept of “success” should be collective as well as individual – it should result in us moderating our personal consumption in favour of a sustainable society.

One of the central tenets of economics for nearly 200 years, the “Tragedy of the Commons“, asserts that individual motives will always overwhelm societal motives and lead to the exhaustion of shared resources, unless those resoures are controlled by a system of private ownership or by government regulation – unless some people or organisations are able to own and control the use of resources by others. We’ll return to this subject shortly, and to its study in the field of Evolutionary Social Biology.

Calling out the failure of the free market: a Three Step Manifesto for Smart Community Economies

If we could answer those three questions, we’d have defined a digital economy in which individual citizens, businesses and communities everywhere would have the skills, opportunities and resources to create their own success on terms that matter to them; and in a way that was beneficial to us all.

That’s the only answer to our current crisis that makes sense to me. It’s not an answer that either Brexit or Donald Trump will help us to find.

So how do we find it?

(The White Horse Tavern in Greenwich Village, New York, one of the city’s oldest taverns. The rich urban life of the Village was described by one of the Taverns’ many famous patrons, the urbanist Jane Jacobs. Photo by Steve Minor).

I think the answers are at our fingertips. In one sense, they’re no more than “nudges” that influence what’s happening already; and they’re supported by robust research in technology, economics, social science, biology and urban design. They lay out a three step manifesto for successful community economies, enabled by technology and rooted in place.

But in another sense, this is a call for fundamental change. These “nudges” will only work if they are enacted as policies, regulations and laws by national and local governments. “Regulation” is a dirty word to the proponents of free markets; but free markets are failing us, and it’s time we admitted that, and shaped them to our needs.

A global-local economy

Globalisation is inevitable – and in many ways beneficial; but ironically the same technologies that enable it can also enable localism, and the two trends do not need to be mutually exclusive.

Many urban designers and environmental experts believe that the best path to a healthy, successful, sustainable and equitable future economy and society lies in a combination of medium density cities with a significant proportion of economic activity (from food to manufacturing to energy to re-use and recycling) based on local transactions supported by walking and cycling.

The same “platform” business models employed by Über, Airbnb and so on could in theory provide the new transaction infrastructure to stimulate and enable such economies. In fact, I believe that they are unique in their ability to do so. Examples already exist – “Borroclub“, for instance, whose platform business connects people who need tools to do jobs with near neighbours who own tools but aren’t using them at the time. A community that adopts Borroclub spends less money on tools; exchanges the money it does spend locally rather than paying it to importers; accomplishes more work using fewer resources; and undertakes fewer car journeys to out-of-town DIY stores.

This can only be accomplished using social digital technology that allows us to easily and cheaply share information with hundreds or thousands of neighbours about what we have and what we need. It could never have happened using telephones or the postal system – the communication technologies of the pre-internet age.

This could be a tremendously powerful way to address the crisis we are facing. Businesses using this model could create jobs, reinforce local social value, reduce the transport and environmental impact of economic transactions and promote the sustainable use of resources; all whilst tapping into the private sector investment that supports growing businesses.

But private sector businesses will only drive social outcomes at scale if we shape the markets they operate in to make that the most profitable business agenda to pursue. The fact that we haven’t shaped the market yet is why platform businesses are currently driving inequality.

There are three measures we could take to shape the market; and the best news is that the first one is already being taken.

1. Legislate to encourage and support social innovation with Open Data and Open Technology

The Director of one of the UK’s first incubators for technology start-up businesses recently told me that “20 years ago, the only way we could help someone to start a business was to help them write a better business plan in order to have a better chance of getting a bank loan. Today there are any number of ways to start a business, and lots of them don’t need you to have much money.”

Technologies such as smartphones, social media, cloud computing and open source software have made it possible to launch global businesses and initiatives almost for free, in return for little more than an investment of time and a willingness to learn new skills. Small-scale innovation has never before had access to such free and powerful tools.

These are all examples of what was originally described as “Intermediate Technology” by the economist Ernst Friedrich “Fritz” Schumacher in his influential work, “Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered“, and is now known as Appropriate Technology.

Schumacher’s views on technology were informed by his belief that our approach to economics should be transformed “as if people mattered”. He asked:

“What happens if we create economics not on the basis of maximising the production of goods and the ability to acquire and consume them – which ends up valuing automation and profit – but on the Buddhist definition of the purpose of work: “to give a man a chance to utilise and develop his faculties; to enable him to overcome his ego-centredness by joining with other people in a common task; and to bring forth the goods and services needed for a becoming existence.”

Schumacher pointed out that the most advanced technologies, to which we often look to create value and growth, are in fact only effective in the hands of those with the resources and skills required to use them – i.e. those who are already wealthy. Further, by emphasising efficiency, output and profit those technologies tend to further concentrate economic value in the hands of the wealthy – often specifically by reducing the employment of people with less advanced skills and roles.

His writing seems prescient now.

A perfect current example is the UK Government’s strategy to drive economic growth by making the UK an international leader in autonomous vehicles, to counter the negative economic impacts of leaving the European Union. That strategy is based on further increasing the number of highly skilled technology and engineering jobs at companies and research insitutions already involved in the sector; and on the UK’s relative lack of regulations preventing the adoption of such technology on the country’s roads.

The strategy will benefit those people with the technological and engineering skills needed to create improvements in autonomous vehicle technology. But what will happen to the far greater number of people who earn their living simply by driving vehicles? They will first see their income fall, and second see their jobs disappear, as technology firstly replaces their permanent jobs with casual labour through platforms such as Über, and secondly completely removes their jobs from the economy by replacing them with self-driving technology. The UK economy might grow in the process; but vast numbers of ordinary people will see their jobs and incomes disappear or decline.

From the broad perspective of the UK workforce, that strategy would be great if we were making a massive investment in education to enable more people to earn a living as highly paid engineers rather than an average or low-paid living as drivers. But of course we’re not doing that at all; at best our educational spend per student is stagnant, and at worst it’s declining as class-sizes grow and we reduce the number of teaching assistants we employ.

In contrast, Schumacher felt that the most genuine “development ” of our society would occur when the most possible people were employed in a way that gave them the practical ability to earn a living; and that also offered a level of human reward – much as Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs” first identifies our most basic requirements for food, water, shelter and security; but next relates the importance of family, friends and “self-actualisation” (which can crudely be described as the process of achieving things that we care about).

This led him to ask:

“What is that we really require from the scientists and technologists? I should answer:

We need methods and equipment which are:

- Cheap enough so that they are accessible to virtually everyone;

- Suitable for small-scale application; and

- Compatible with man’s need for creativity”

These are precisely the characteristics of the Cloud Computing, social media, Open Source and smartphone technologies that are now so widely available, and so astonishingly powerful. What we need to do next is to provide more support to help people everywhere put them to use for their own purposes.

Firstly, Open data, open algorithms and open APIs should be mandatory for any publicly funded service or infrastructure. They should be included in the procurement criteria for services and goods procured on behalf of the public sector. Our public infrastructure should be digitally open, accessible and accountable.

Secondly, some of the proceeds from corporate taxation – whether at national level or from local business rates – should be used to provide regional investment funds to support local businesses and social enterprises that contribute to local social, economic and environmental objectives; and to support the regional social innovation communities such as the network of Impact Hubs that help such initiatives start, succeed and grow.

But perhaps most importantly, those proceeds should also be used to fund improvements to state education everywhere. People can only use tools if they are given the opportunity to acquire skills; and as tools and technologies change, we need the opportunity to learn new skills. If our jobs – or more broadly our roles in society – are not ultimately to be replaced by machines, we need to develop the creativity to use those tools to create the human value that technology will never understand.

It is surely insane that we are pouring billions of pounds and dollars into the development of technologies that mean we need to develop new skills in order to remain employable, and that those investments are making our economy richer and richer; but that at the same time we are making a smaller and smaller proportion of that wealth available to educate our children.

Just as some of the profits of the Industrial Revolution were spent on infrastructure with a social purpose, so should some of the profits of the Information Revolution be.

2. Legislate to encourage and support business models with a positive social outcome

The social quality of the behaviour of private sector businesses varies enormously.

The story of Hancock Bank’s actions to assist the citizens of New Orleans to recover from hurricane Katrina in 2005 – by lending cash to anyone who needed it and was prepared to sign an IoU – is told in this video, and is an extraordinary example of responsible business behaviour. In an unprecedented situation, the Bank’s leaders based their decisions on the company’s purpose, expressed in its charter, to support the communities of the city. This is in contrast to the behaviour of Bob Diamond, who resigned as CEO of Barclays Bank following the LIBOR rate-manipulation scandal, and who under questioning by parliamentary committee could not remember what the Bank’s founding principles, written by community-minded Quakers, stated.

Barclays’ employees’ behaviour under Bob Diamond was driven purely by the motivation to earn bigger bonuses by achieving the Bank’s primary objective, to increase shareholder value.

But the overriding focus on shareholders as the primary stakeholder in private sector business is relatively new. Historically, customers and employees have been treated as equally important. Some leading economists now believe we should return to such balanced models.

There are already models of business – such as “social enterprise” – which promote more balanced corporate governance, and that even offer accreditation schemes. We could incentivise such models to be more successful in our economy by creating a preferential market for them – lower rates of taxation; preferential scoring in public sector procurements; and so on.

An alternative is to use technology to enable entirely new, entirely open systems. “Blockchains” are the technology that enable the digital currency “Bitcoin“. The Bitcoin Blockchain is a single, distributed ledger that records every Bitcoin transaction so that anyone in the world can see it. So unlike the traditional system of money in which we depend on physical tokens, banks and payment services to define the ownership of money and to govern transactions, Bitcoin transactions work because everybody can see who owns which Bitcoins and when they’re being exchanged.

This principle of a “distributed, open ledger” – implemented by a blockchain – is thought by many technology industry observers to be the most important, powerfully disruptive invention since the internet. The Ethereum “smart contracts” platfom adds behaviour to the blockchain – open algorithms that cannot be tampered with and that dictate how transactions take place and what happens as a consequence of them. It is leading to some strikingly different new business models, including the “Distributed Autonomous Organisation” (or “DAO” for short), a multi-$million investment fund that is entirely, democratically run by smart contracts on behalf of its investors.

By promoting distributed, non-repudiatable transparency in this way, blockchain technologies offer unprecedented opportunities to ensure that all of the participants in an economic system have the opportunity to influence the distribution of the benefits of the system in a fair way. This idea is already at the heart of an array of initiatives to ensure that some of the least wealthy people in the world benefit more fairly from the information economy.

Finally, research in economics and in evolutionary social biology is yielding prescriptive insights into how we can design business models that are as wildly successful as those of Über and Airbnb, but with models of corporate governance that ensure that the wealth they create is more broadly and fairly distributed.

In conversation with a researcher at Imperial College London a few years ago, I said that I thought we needed to find criteria to distinguish “platform” businesses like Casserole Club that create social value from those like Über that concentrate the vast majority of the wealth they create in the hands of the platform owners. (Casserole Club uses social media to match people who are unable to provide meals for themselves with neighbours who are happy to cook and share an extra portion of their meal).

The researcher told me I should consult Elinor Ostrom’s work in Economics. Ostrom, who won the Nobel prize in 2009, spent her life working with communities around the world who successfully manage shared resources (land, forests, fresh water, fisheries etc.) sustainably, and writing down the common features of their organisational models. Her Nobel prize was awarded for using this evidence to disprove the “tragedy of the commons” doctrine which economists previously believed proved that sustainable commons management was impossible.

Most of Ostrom’s principles for organisational design and behaviour are strikingly similar to the models used by platform businesses such as Über and Airbnb. But the principles she discovered that are the most interesting are the ones that Über and Airbnb don’t follow – the price of exchange being agreed by all of the participants in a transaction, for example, rather than it being set by the platform owner. Ostrom’s work has been continued by David Sloan Wilson who has demonstrated that the principles she discovered follow from evolutionary social biology – the science that studies the evolution of human social behaviour.

Elinor Ostrom’s design principles for commons organisations offer us not only a toolkit for the design of successful, socially responsible platform businesses; they offer us a toolkit for their regulation, too, by specifying the characteristics of businesses that we should preferentially reward through market regulation and tax policy.

3. Legislate for individual ownership of personal data, and a right to share in the profits it creates.

Platform business models may depend less and less on our labour – or at least, may have found ways to pay less for it as a proportion of their profits; but they depend absolutely on our data.

Of course, we – usually – get some value in return for our data – useful search results, guidance to the quickest route to our journey, recommendations of new songs, films or books we might like.

But is massive inequality really a price worth paying for convenience?

The ownership of private property and intellectual property underpin the capitalist economy, which until recently was primarily based on the value of physical assets and closed knowledge, made difficult to replicate through being stored primarily in physical, analogue media (including our brains).

Our economy is now being utterly transformed by easy to replicate, easy to transfer digital data – from news to music to video entertainment to financial services, business models that had operated for decades have been swept away and replaced by models that are constantly adapting, driven by advances in technology.

But data legislation has not kept pace. Despite several revisions of data protection and privacy legislation, the ownership of digital data is far from clearly defined in law, and in general its exchange is subject to individual agreements between parties.

It is time to legislate more strongly that the value of the data we create by our actions, our movement and our communication belongs to us as individuals, and that in turn we receive a greater share of the profits that are made from its use.

That is the more likely mechanism to result in the fair distribution of value in the economy as the value of labour falls than a Universal Basic Income that rewards nothing.

One last plea to our political leaders to admit that we face a crisis

Whilst the UK and the USA argue – and even riot – about the outcomes of the European Union referendum and the US Presidential election, the issues of inequality, loss of jobs and disenfranchisement from the political system are finally coming to light in the media.

But it’s a disgrace that they barely featured at all in either of those campaigns.

Emotionally right now I want to castigate our politicians for getting us into this mess through all sorts of venality, complacency, hubris and untruthfulness. But two things I know they are not – including Donald Trump – are stupid or ignorant. They surely must be aware of these issues – why will they not recognise and address them?

Robert Wright’s mathematical analysis of the evolution of human society, NonZero, describes the emergence of our current model of nation states through the European Middle Ages as a tension between the ruling and working classes. The working classes pay a tax to the ruling classes, who they accept will live a wealthier life, in return for a safe and peaceful environment in which to live. Whenever the price paid for safety and peace grew unreasonably high, the working classes revolted and overthrew the ruling classes, resulting eventually in a new, better-balanced model.

Is it scaremongering to suggest we are close to a similar era of instability?

I don’t think so. At the same time that the Industrial Revolution created widespread economic growth and improvements in prosperity, it similarly exacerbated inequality between the general population and the property- and business-owning elite. Just as I have argued in this article, that inequality was corrected not by “big government” and grand top-down redistributive schemes, but by measures that shaped markets and investments in education and enablement for the wider population.

We have not yet taken those corrective actions for the Information Revolution – nor even realised and acknowledged that we need to take them. Inequality is rising as a consequence, and it is widely appreciated that inequality creates social unrest.

Brexit and the election of Donald Trump following a campaign of such obvious lies, misogyny and – at best – narrow-minded nationalism are unprecedented in modern times. They have already resulted in social unrest in the form of riots and increased incidents of racism – as has the rise in the price of staple food caused by severe climate events as a vast number of people around the world struggle to feed themselves when hurricanes and droughts affect the production of basic crops. It’s no surprise that the World Economic Forum’s 2016 Global Risks Report identifies “unemployment and underemployment” and “profound social instability” as amongst the top 10 most likely and impactful global risks facing the world.

Brexit and Donald Trump are not crises in themselves; but they are symptoms of a real crisis that we face now; and until we – and our political leaders – face up to that and start dealing with it properly, we are putting ourselves, our future and our childrens’ future at unimaginable risk.

Thankyou to the following, whose opinions and expertise, expressed in articles and conversations, helped me to write this post:

- Tom Baker, who introduced me to the power of social enterprise as a business model for improving communities when he was CIO at Sunderland City Council

- The architect and urban designer Kelvin Campbell, founder of the Smart Urbanism movement and “Massive / Small change“

- Indy Johar, the inspirational founder of the global Impact Hub network

- Jeremy Pitt of Imperial College, who first introduced me to Elinor Ostrom’s work

- David Sloan Wilson who shared with me the principles from evolutionary social biology that he discovered underpin Elinor Ostrom’s work

- Leo Johnson, who first introduced me to the work of E.F. Schumacher through a debate on responsible business

- Andy McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, who I was lucky enough to meet at a conference dinner, and whose book “The Second Machine Age” first convinced me we should take these issues seriously; along with their colleague Marshall Van Alstyne, an expert on platform business models

- Azeem Azhar, curator of the Exponential View, probably the best regular source of social and technology insight on the web