Seven steps to a Smarter City; and the imperative for taking them (updated 8th September 2013)

September 8, 2013 4 Comments

(Interior of the new Library of Birmingham, opened in September 2013. Photo by Andy Mabbett licensed under Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons)

(This article originally appeared in September 2012 as “Five steps to a Smarter City: and the philosophical imperative for taking them“. Because it contains an overall framework for approaching Smart City transformations, I keep it updated to reflect the latest content on this blog; and ongoing developments in the industry. It can also be accessed through the page link “Seven steps to a Smarter City” in the navigation bar above).

As I’ve worked with cities over the past two years developing their “Smarter City” strategies and programmes to deliver them, I’ve frequently written articles on this blog exploring the main challenges they’ve faced: establishing a cross-city consensus to act; securing funding; and finding the common ground between the institutional and organic natures of city ecosystems.

We’ve moved beyond exploration now. There are enough examples of cities making progress on the “Smart” agenda for us to identify the common traits that lead to success. I first wrote “Five steps to a Smarter City: and the philosophical imperative for taking them” in September 2012 to capture what at the time seemed to be emerging practises with promising potential, and have updated it twice since then. A year later, it’s time for a third and more confident revision.

In the past few months it’s also become clear that an additional step is required to recognise the need for new policy frameworks to enable the emergence of Smarter City characteristics, to complement the direct actions and initiatives that can be taken by city institutions, businesses and communities.

The revised seven steps involved in creating and achieving a Smarter City vision are:

- Define what a “Smarter City” means to you (Updated)

- Convene a stakeholder group to co-create a specific Smarter City vision; and establish governance and a credible decision-making process (Updated)

- Structure your approach to a Smart City by drawing on the available resources and expertise (Updated)

- Establish the policy framework (New)

- Populate a roadmap that can deliver the vision (Updated)

- Put the financing in place (Updated)

- Enable communities and engage with informality: how to make “Smarter” a self-sustaining process (Updated)

I’ll close the article with a commentary on a new form of leadership that can be observed at the heart of many of the individual initiatives and city-wide programmes that are making the most progress. Described by Andrew Zolli in “Resilience: why things bounce back” as “translational leadership“, it is characterised by an ability to build unusually broad collaborative networks across the institutions and communities – both formal and informal – of a city.

But I’ll begin with what used to be the ending to this article: why Smarter Cities matter. Unless we’re agreed on the need for them, it’s unlikely we’ll take the steps required to achieve them.

(Why Smarter Cities matter: “Lives on the Line” by James Cheshire at UCL’s Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis, showing the variation in life expectancy across London. From Cheshire, J. 2012. Lives on the Line: Mapping Life Expectancy Along the London Tube Network. Environment and Planning A. 44 (7). Doi: 10.1068/a45341)

I think it’s vitally important to take a pro-active approach to Smarter Cities.

According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs’ 2011 revision to their “World Urbanisation Prospects” report, between now and 2050 the world’s population will rise by 2-3 billion. The greatest part of that rise will be accounted for by the growth of Asian, African and South American “megacities” with populations of between 1 and 35 million people.

As a crude generalisation, this unprecedented growth offers four challenges to cities in different circumstances:

- For rapidly growing cities: we have never before engineered urban infrastructures to support such growth. Whenever we’ve tried to accommodate rapid urban growth before, we’ve failed to provide adequate infrastructure, resulting in slums. One theme within Smarter Cities is therefore the attempt to use technology to respond more successfully to this rapid urbanisation.

- For cities in developed economies with slower growth: urbanisation in rapidly growing economies is creating an enormous rise in the size of the world’s middle-class, magnifying global growth in demand for resources such as energy, water, food and materials; and creating new competition for economic activity. So a second theme of Smarter Cities that applies in mature economies is to remain vibrant economically and socially in this context, and to improve the distribution of wealth and opportunity, against a background of modest economic growth, ageing populations with increasing service needs, legacy infrastructure and a complex model of governance and operation of city services.

- For cities in countries that are still developing slowly: increasing levels of wealth and economic growth elsewhere create an even tougher hurdle than before in creating opportunity and prosperity for the populations of those countries not yet on the path to growth. At the same time that economists and international development organisations attempt to ensure that these nations benefit from their natural resources as they are sought by growing economies elsewhere, a third strand of Smarter Cities is concerned with supporting wider growth in their economies despite a generally low level of infrastructure, including technology infrastructure.

- For cities everywhere: as our population becomes increasingly concentrated in cities, and as human activity causes the world to become warmer, extreme weather events and natural disasters are not only becoming more frequent; their impact and cost are rising. If this sounds alarmist, consider the frightening global effects of recent grain shortages caused by drought in the US. The supply chains that provide food and resources to city populations are vast and sophisticated, but still vulnerable to disruption – in the 2000 strike by the drivers who deliver fuel to petrol stations in the UK, some city supermarkets came within hours of running out of food completely. So a fourth theme of Smarter Cities is to engineer more efficient, resilient infrastructure and supply chains to support cities everywhere.

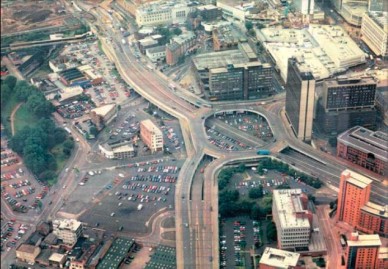

(Photo of Masshouse Circus, Birmingham, a concrete urban expressway that strangled the citycentre before its redevelopment in 2003, by Birmingham City Council)

We have only been partly successful in meeting these challenges in the past. As public and private sector institutions in Europe and the United States evolved through the previous period of urbanisation driven by the Industrial Revolution they achieved mixed results: standards of living rose dramatically; but so unequally that life expectancy between the richest and poorest areas of a single UK city often varies by 10 to 20 years.

In the sense that city services and businesses will always seek to exploit the technologies available to them, our cities will become smarter eventually as an inevitable consequence of the evolution of technology and growing competition for resources and economic activity.

But if those forces are allowed to drive the evolution of our cities, rather than supporting a direction of evolution that is proactively chosen by city stakeholders, then we will not solve many of the challenges that we care about most: improving the distribution of wealth and opportunity, and creating a better, sustainable quality of life for everyone. As I argued in “Smarter City myths and misconceptions“, “business as usual” will not deliver what we want and need – we need new approaches.

I do not pretend that it will be straightforward to apply our newest tool – digital technology – to achieve those objectives. In “Death, Life and Place in Great Digital Cities“, I explored the potential for unintended consequences when applying technology in cities, and compared them to the ongoing challenge of balancing the impacts and benefits of the previous generations of technology that shaped the cities we live in today – elevators, concrete and the internal combustion engine. Those technologies enabled the last century of growth; but in some cases have created brutal and inhumane urban environments which limit the quality of life that is possible within them.

But there are nevertheless many ways for cities in every circumstance imaginable to benefit from Smarter City ideas, as I described in my presentation earlier this year to the United Nations Commission on Science and Technology for Development, “Science, technology and innovation for sustainable cities and peri-urban communities“.

The first step in doing so is for each city and community to decide what “Smarter Cities “means to them.

(A prediction of traffic speed and volume 30 minutes into the future in Singapore. In a city with a growing economy and a shortage of space, the use of technology to enable an efficient transportation system has long been a priority)

1. Define what a “Smarter City” means to you

Many urbanists and cities have grappled with how to define what a “Smart City”, a “Smarter City” or a “Future City” might be. It’s important for cities to agree to use an appropriate definition because it sets the scope and focus for what will be a complex collective journey of transformation.

In his article “The Top 10 Smart Cities On The Planet“, Boyd Cohen of Fast Company defined a Smart City as follows:

“Smart cities use information and communication technologies (ICT) to be more intelligent and efficient in the use of resources, resulting in cost and energy savings, improved service delivery and quality of life, and reduced environmental footprint–all supporting innovation and the low-carbon economy.”

IBM describes a Smarter City in similar terms, more specifically stating that the role of technology is to create systems that are “instrumented, interconnected and intelligent.”

Those definitions are useful; but they don’t reflect the different situations of cities everywhere, which are only very crudely described by the four contexts I identified above. We should not be critical of any of the general definitions of Smarter Cities; they are useful in identifying the nature and scope of powerful ideas that could have widespread benefits. But a broad definition will never provide a credible direction for any individual city given the complexities of its challenges, opportunities, context and capabilities.

Additionally, definitions of “Smarter Cities” that are based on relatively advanced technology concepts don’t reflect the origins of the term “Smart” as recognised by the social scientists I met with in July at a workshop at the University of Durham. The “Smart” idea is more than a decade old, and emerged from the innovative use of relatively basic digital technologies to stimulate economic growth, community vitality and urban renewal.

As I unifying approach, I’ve therefore come recently to conceive of a Smarter City as follows:

A Smarter City systematically creates and encourages innovations in city systems that are enabled by technology; that change the relationships between the creation of economic and social value and the consumption of resources; and that contribute in a coordinated way to achieving a vision and clear objectives that are supported by a consensus amongst city stakeholders.

In co-creating a consensual approach to “Smarter Cities” in any particular place, it’s important to embrace the richness and variety of the field. Many people are very sceptical of the idea of Smarter Cities; often I find that their scepticism arises from the perception that proponents of Smarter Cities are intent on applying the same ideas everywhere, regardless of their suitability, as I described in Smarter City myths and misconceptions” in July.

For example, highly intelligent, multi-modal transport infrastructures are vital in cities such as Singapore, where a rapidly growing economy has created an increased demand for transport; but where there is no space to build new road capacity. But they are much less relevant – at least in the short term – for cities such as Sunderland where the priority is to provide better access to digital technology to encourage the formation and growth of new businesses in high-value sectors of the economy. Every city, individual or organisation that I know of that is successfully pursuing a Smarter City initiative or strategy recognises and engages with that diversity,

Creating a specific Smarter City vision is therefore a task for each city to undertake for itself, taking into account its unique character, strengths and priorities. This process usually entails a collaborative act of creativity by city stakeholders – I’ll explore how that takes place in the next section.

To conclude, it’s likely that the following generic objectives should be considered and adapted in that process:

- A Smarter City is in a position to make a success of the present: for example, it is economically active in high-value industry sectors and able to provide the workforce and infrastructure that companies in those sectors need.

- A Smarter City is on course for a successful future: with an education system that provides the skills that will be needed by future industries as technology evolves.

- A Smarter City creates sustainable, equitably distributed growth: where education and employment opportunities are widely available to all citizens and communities, and with a focus on delivering social and environmental outcomes as well as economic growth.

- A Smarter City operates as efficiently & intelligently as possible: so that resources such as energy, transportation systems and water are used optimally, providing a low-cost, low-carbon basis for economic and social growth, and an attractive, healthy environment in which to live and work.

- A Smarter City enables citizens, communities, entrepreneurs & businesses to do their best; because making infrastructures Smarter is an engineering challenge; but making cities Smarter is a societal challenge; and those best placed to understand how societies can change are those who can innovate within them.

- A Smarter City harnesses technology effectively and makes it accessible; because technology continues to define the new infrastructures that are required to achieve efficiencies in operation; and to enable economic and social growth.

(The members of Birmingham’s Smart City Commission)

2. Convene a stakeholder group to co-create a specific Smarter City vision

For a city to agree a shared “Smarter City” vision involves bringing an unusual set of stakeholders together in a single forum: political leaders, community leaders, major employers, transport and utility providers, entrepreneurs and SMEs, universities and faith groups, for example. The task for these stakeholders is to agree a vision that is compelling, inclusive; and specific enough to drive the creation of a roadmap of individual projects and initiatives to move the city forward.

It’s crucial that this vision is co-created by a group of stakeholders; as a city leader commented to me last year: “One party can’t bring the vision to the table and expect everyone else to buy into it”.

This is a process that I’m proud to be taking part in in Birmingham through the City’s Smart City Commission, whose vision for the city was published in December. I discussed how such processes can work, and some of the challenges and activities involved, in July 2012 in an article entitled “How Smarter Cities Get Started“.

To be sufficiently creative, empowered and inclusive, the group of stakeholders needs to encompass not only the leaders of key city institutions and representatives of its breadth of communities; it needs to contain original thinkers; social entrepreneurs and agents of change. As someone commented to me recently following a successful meeting of such a group: “this isn’t a ‘usual’ group of people”. In a similar meeting this week, a colleague likened the process of assembling such a group to that of building the Board of a new company.

To attract the various forms of investment that are required to support a programme of “Smart” initiatives, these stakeholder groups need to be decision-making entities, such as Manchester’s “New Economy” Commission, not discussion forums. They need to take investment decisions together in the interest of shared objectives; and they need a mature understanding and agreement of how risk is shared and managed across those investments.

Whatever specific form a local partnership takes, it needs to demonstrate transparency and consistency in its decision-making and risk management, in order that its initiatives and proposals are attractive to investors. These characteristics are straightforward in themselves; but take time to establish amongst a new group of stakeholders taking a new, collaborative approach to the management of a programme of transformation.

Finally, to create and execute a vision that can succeed, the group needs to tell stories. A Smarter City encompasses all of a city’s systems, communities and businesses; the leaders in that ecosystem can only act with the support of their shareholders, voters, citizens, employees and neighbours. We will only appeal to such a broad constituency by telling simple stories that everyone can understand. I discussed some of the reasons that lead to this in “Better stories for Smarter Cities: three trends in urbanism that will reshape our world” in January and “Little/big; producer/consumer; and the story of the Smarter City” in March. Both articles cover similar ground; and were written as I prepared for my TEDxWarwick presentation, “Better Stories for Smarter Cities”, also in March.

The article “Smart ideas for everyday cities” from December 2012 discusses all of these challenges, and examples of groups that have addressed them, in more detail.

3. Structure your approach to a Smart City by drawing on the available resources and expertise

Any holistic approach to a Smarter City needs to recognise the immensely complex context that a city represents: a rich “system of systems” comprising the physical environment, economy, transport and utility systems, communities, education and many other services, systems and human activities.

(The components of a Smart City architecture I described in “The new architecture of Smart Cities“)

In “The new architecture of Smart Cities” in September 2012 I laid out a framework for thinking about that context; in particular highlighting the need to focus on the “soft infrastructure” of conversations, trust, relationships and engagement between people, communities, enterprises and institutions that is fundamental to establishing a consensual view of the future of a city.

In that article I also asserted that whilst in Smarter Cities we are often concerned with the application of technology to city systems, the context in which we do so – i.e. our understanding of the city as a whole – is the same context as that in which other urban professionals operate: architects, town planners and policy-makers, for example. An implication is that when looking for expertise to inform an approach to “Smarter Cities”, we should look broadly across the field of urbanism, and not restrict ourselves to that material which pertains specifically to the application of technology to cities.

Formal sources include:

- The City Protocol Society, which seems to be the strongest emerging initiative to determine frameworks and standards for approaching Smarter Cities. The UK is establishing one of three local charters to the society.

- UN-HABITAT, the United Nations agency for human settlements, which recently published its “State of the World’s Cities 2012/2013” report. UNHABITAT promote socially and environmentally sustainable towns and cities, and their reports and statistics on urbanisation are frequently cited as authoritative. Their 2012/2013 report includes extensive consultation with cities around the world, and proposes a number of new mechanisms intended to assist decision-makers.

- The World Bank, whose Urban Development page contains a number of reports covering many aspects of urbanisation relevant to Smarter Cities, such as “Transforming Cities with Transit”, “Urban Risk Assessments: Towards a Common Approach” and “Building Sustainability in an Urbanising World“.

- The Academy of Urbanism, a UK-based not-for-profit association of several hundred urbanists including policy-makers, architects, planners and academics, publishes the “Friebrug Charter for Sustainable Urbanism” in collaboration with the city of Frieburg, Germany. Frieburg won the Academy’s European City of the Year award in 2010 but its history of recognition as a sustainable city goes back further. The charter contains a number of useful principles and ideas for achieving consensual sustainability that can be applied to Smarter Cities.

- Academic initiatives investigating the technologies and business models for integrated, sustainable city systems such as Imperial College’s Digital City Exchange; or international collaborations including the Urban Systems Collaborative and the Centre for Urban Science and Progress, led by New York University and involving IBM Research and the University of Warwick amongst others.

- At a more technical level, the European Union Platform for Intelligent Cities (EPIC) project, in which IBM and Birmingham City University are amongst the participants, and the “FI-WARE” project, also funded by the European Union, are researching the architectures and standards for Smarter Cities and “future internet” platforms. One of FI-WARE’s focusses is how cities can provide technology infrastructures on which SMEs and entrepreneurs can base innovative new city services, an idea I have called an “innovation boundary” and have argued should be at the heart of a Smarter City.

- The UK Technology Strategy Board’s “Future Cities” programme (link requires registration) and the ongoing EU investments in Smart Cities are both investing in initiatives that transfer Smarter City ideas and technology from research into practise, and disseminating the knowledge created in doing so.

- Consultancies, technology and service providers also offer useful views. IBM’s perspectives and case studies can be found at http://www.ibm.com/smartercities/; Arup have published a number of viewpoints, including “Information Marketplaces: the new economics of cities“; and McKinsey’s recent reports “Government designed for new times: a global conversation” and “How to make a city great” contain a number of sections dedicated to technology and Smarter Cities.

(Photo by lecercle of a girl in Mumbai doing her homework on whatever flat surface she could find. Her use of a stationary tool usually employed for physical mobility to enhance her own social mobility is an example of the very basic capacity we all have to use the resources available to us in innovative ways)

It is also important to consider how change is achieved in systems as complex as cities. In “Do we need a Pattern Language for Smarter Cities” I noted some of the challenges involve in driving top-down programmes of change; and contrasted them to what can happen when an environment is created that encourages innovation and attempts to influence it to achieve desired outcomes, rather than to adopt particular approaches to doing so. And in “Zen and the art of messy urbanism” I explored the importance of unplanned, informal and highly creative “grass-roots” activity in creating growth in cities, particularly where resources and finances are constrained.

Some very interesting such approaches have emerged from thinking in policy, economics, planning and architecture: the Collective Research Initiatives Trust‘s study of Mumbai, “Being Nicely Messy“; Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter’s “Collage City“; Manu Fernandez’s “Human Scale Cities” project; and the “Massive / Small” concept and associated “Urban Operating System” from Kelvin Campbell and Urban Initiatives, for example have all suggested an approach that involves a “toolkit” of ideas for individuals and organisations to apply in their local context.

The “tools” in such toolkits are similar to the “design patterns“ invented by the town planner Christopher Alexander in the 1970s as a tool for capturing re-usable experience in town planning, and later adopted by the Software industry. I believe they offer a useful way to organise our knowledge of successful approaches to “Smarter Cities”, and am slowly creating a catalogue of them, including the “City information partnership” and “City-centre enterprise incubation“.

A good balance between the top-down and bottom-up approaches can be found in the large number of “Smart Cities” and “Future Cities” communities on the web, such as UBM’s “Future Cities” site; Next City; the Sustainable Cities Collective; the World Cities Network; and Linked-In discussion Groups including “Smart Cities and City 2.0“, “Smarter Cities” and “Smart Urbanism“.

Finally, I published an extensive article on this blog in December 2012 which provided a framework for identifying the technology components required to support Smart City initiatives of different kinds – “Pens, paper and conversations. And the other technologies that will make cities smarter“.

4. Establish the policy framework

The influential urbanist Jane Jacobs wrote in her seminal 1961 work ”The Death and Life of Great American Cities“:

“Private investment shapes cities, but social ideas (and laws) shape private investment. First comes the image of what we want, then the machinery is adapted to turn out that image. The financial machinery has been adjusted to create anti-city images because, and only because, we as a society thought this would be good for us. If and when we think that lively, diversified city, capable of continual, close- grained improvement and change, is desirable, then we will adjust the financial machinery to get that.”

Jacobs’ was concerned with redressing the focus of urban design away from vehicle traffic and back to meeting the daily requirements of human lives; but today, it is similarly true that our planning and procurement practises do not recognise the value of the Smart City vision, and therefore are not shaping the financial instruments to deliver it. This is not because those practises are at fault; it is because technologists, urbanists, architects, procurement officers, policy-makers and planners need to work together to evolve those practises to take account of the new possibilities available to cities through technology.

It’s vitally important that we do this. As I described in November 2012 in “No-one is going to pay cities to become Smarter“, the sources of research and innovation funding that are supprting the first examples of Smarter City initiatives will not finance the widespread transformation of cities everywhere. But there’s no need for them to: the British Property Federation, for example, estimate that £14 billion is invested in the development of new space in the UK each year – that’s 500 times the annual value of the UK Government’s Urban Broadband Fund. If planning regulations and other policies can be adapted to promote investment in the technology infrastructures that support Smarter Cities, the effect could be enormous.

I ran a workshop titled “Can digital technology help us build better cities?” to explore these themes in May at the annual Congress of the Academy of Urbanism in Bradford; and have been exploring them with a number of city Councils and institutions such as the British Standards Institute throughout the year. In June I summarised the ideas that emerged from that work in the article “How to build a Smarter City: 23 design principles for digital urbanism“.

Two of the key issues to address are open data and digital privacy.

As I explored in “Open urbanism: why the information economy will lead to sustainable cities” in December 2012, open data is a vital resource for creating successful, sustainable, equitable cities. But there are thousands of datasets relevant to any individual city; owned by a variety of public and private sector institutions; and held in an enormous number of fragmented IT systems of varying ages and designs. Creating high quality, consistent, reliable data in this context is a “Brownfield regeneration challenge for the information age”, as I described in October 2012. Planning and procurement regulations that require city information to be made openly available will be an important tool in creating the investment required to overcome that challenge.

(The image on the right was re-created from an MRI scan of the brain activity of a subject watching the film shown in the image on the left. By Shinji Nishimoto, Alex G. Huth, An Vu and Jack L. Gallant, UC Berkley, 2011)

Digital privacy matters to Smarter Cities in part because technology is becoming ever more fundamental to our lives as more and more of our business is transacted online through e-commerce and online banking. Additionally, the boundary between technology, information and the physical world is increasingly disappearing – as shown recently by the scientists who demonstrated that one person’s thoughts could control another’s actions, using technology, not magic or extrasensory phenomena. That means that our physical safety and digital privacy are increasingly linked – the emergence this year of working guns 3D-printed from digital designs is one of the most striking examples.

Jane Jacobs defined cities by their ability to provide privacy and safety amongst their citizens; and her thinking is still regarded by many urbanists as the basis of our understanding of cities. As digital technology becomes more pervasive in city systems, it is vital that we evolve the policies that govern digital privacy to ensure that those systems continue to support our lives, communities and businesses successfully.

5. Populate a roadmap that can deliver the vision

In order to fulfill a vision for a Smarter City, a roadmap of specific projects and initiatives is needed, including both early “quick wins” and longer term strategic programmes.

Those projects and initiatives take many forms; and it can be worthwhile to concentrate initial effort on those that are simplest to execute because they are within the remit of a single organisation; or because they build on cross-organisational initiatives within cities that are already underway.

In my August 2012 article “Five roads to a Smarter City” I gave some ideas of what those initiatives might be, and the factors affecting their viability and timing, including:

- Top-down, strategic transformations across city systems;

- Optimisation of individual infrastructures such as energy, water and transportation;

- Applying “Smarter” approaches to “micro-city” environments such as industrial parks, transport hubs, university campuses or leisure complexes;

- Exploiting the technology platforms emerging from the cost-driven transformation to shared services in public sector;

- Supporting the “Open Data” movement.

In “Pens, paper and conversations. And the other technologies that will make cities smarter” in December 2012, I described a framework for identifying the technology components required to support Smart City initiatives of different kinds, such as:

- Re-engineering the physical components of city systems (to improve their efficiency)

- Using information to optimise the operation of city systems

- Co-ordinating the behaviour of multiple systems to contribute to city-wide outcomes

- Creating new marketplaces to encourage sustainable choices, and attract investment

The Smarter City design patterns I described in the previous section also provide potential ideas, including City information partnerships and City-centre enterprise incubation; I’m hoping shortly to add new patterns such as Community Energy Initiatives, Social Enterprises, Local Currencies and Information-Enabled Resource Marketplaces.

It is also worthwhile to engage with service and technology providers in the Smart City space; they have knowledge of projects and initiatives with which they have been involved elsewhere. Many are also seeking suitable locations in which to invest in pilot schemes to develop or prove new offerings which, if successful, can generate follow-on sales elsewhere. The “First of a Kind” programme in IBM’s Research division is one example or a formal programme that is operated for this purpose.

A roadmap consisting of several such individual activities within the context of a set of cross-city goals, and co-ordinated by a forum of cross-city stakeholders, can form a powerful programme for making cities Smarter.

(Photo of the Brixton Pound by Charlie Waterhouse)

6. Put the financing in place

A crucial factor in assessing the viability of those activities, and then executing them, is putting in place the required financing. In many cases, that will involve cities approaching investors or funding agencies. In “Smart ideas for everyday cities” in December 2012 I described some of the organisations from whom funds could be secured; and some of the characteristics they are looking for when considering which cities and initiatives to invest in.

But for cities to seek direct funding for Smarter Cities is only one approach; I compared it to four other approaches in “Gain and responsibility: five business models for sustainable cities” in August:

- Cross-city Collaborations

- Scaling-up Social Enterprise

- Creativity in finance

- Making traditional business sustainable

- Encouraging entrepreneurs everywhere

The role of traditional business is of particular importance. Billions of us depend for our basic needs – not to mention our entertainment and leisure – on global supply chains operated on astounding scales by private sector businesses. Staples such as food, cosmetics and cleaning products consume a vast proportion of the world’s fresh water and agricultural capacity; and a surprisingly small number of organisations are responsible for a surprisingly large proportion of that consumption as they produce the products and services that many of us use. We will only achieve smarter, sustainable cities, and a smarter, sustainable world, in collaboration with them. The CEOs of Unilever and Tesco have made statements of intent along these lines recently, and IBM and Hilton Hotels are two businesses that have described the progress they have already made.

There are very many individual ways in which funds can be secured for Smart City initiatives, of course; I described some more in “No-one is going to pay cities to become Smarter” in November 2012, and several others in two articles in September 2012:

In “Ten ways to pay for a Smarter City (part one)“:

- Apply for research grants to support new Smarter City ideas;

- Exploit the information-sharing potential of shared service platforms;

- Find and support hidden local innovations;

- Explore the cost-saving potential of Smarter technologies;

- Consider whether some Smarter City initiatives could be sponsored.

And in “Ten ways to pay for a Smarter City (part two):

- Approach ethical investment funds, values-led banks and national lotteries;

- Make procurement Smarter;

- Use legitimate state aid;

- Encourage Open Data and Hacktivism;

- Create new markets.

I’m a technologist, not a financier or economist; so those articles are not intended to be exhaustive or definitive. But they do suggest a number of practical options that can be explored.

(The discussion group at #SmartHack in Birmingham, described in “Tea, trust and hacking – how Birmingham is getting Smarter“, photographed by Sebastian Lenton)

7. Think beyond the future and engage with informality: how to make “Smarter” a self-sustaining process

Once a city has become “Smart”, is that the end of the story?

I don’t think so. The really Smart city is one that has put in place soft and hard infrastructures that can be used in a continuous process of reinvention and creativity.

In the same way that a well designed urban highway should connect rather than divide the city communities it passes through, the new technology platforms put in place to support Smarter City initiatives should be made open to communities and entrepreneurs to constantly innovate in their own local context. As I explored in “Smarter city myths and misconceptions” this idea should really be at the heart of our understanding of Smarter Cities.

I’ve explored those themes frequently in articles on this blog; including the two articles that led to my TEDxWarwick presentation, “Better stories for Smarter Cities: three trends in urbanism that will reshape our world” and “Little/big; producer/consumer; and the story of the Smarter City“. Both of them explored the importance of large city institutions engaging with and empowering the small-scale hyperlocal innovation that occurs in cities and communities everywhere; and that is often the most efficient way of creating social and economic value.

I described that process along with some examples of it in “The amazing heart of a Smarter City: the innovation boundary” in August 2012. In October 2012, I described some of the ways in which Birmingham’s communities are exploring that boundary in “Tea, trust and hacking: how Birmingham is getting smarter“; and in November I emphasised in “Zen and the art of messy urbanism” the importance of recognising the organic, informal nature of some of the innovation and activity within cities that creates value.

The Physicist Geoffrey West is one of many scientists who has explored the roles of technology and population growth in speeding up city systems; as our world changes more and more quickly, our cities will need to become more agile and adaptable – technologists, town planners and economists all seem to agree on this point. In “Refactoring, nucleation and incubation: three tools for digital urban adaptability” I explored how ideas from all of those professions can help them to do so.

Smarter, agile cities will enable the ongoing creation of new products, services or even marketplaces that enable city residents and visitors to make choices every day that reinforce local values and synergies. I described some of the ways in which technology could enable those markets to be designed to encourage transactions that support local outcomes in “Open urbanism: why the information economy will lead to sustainable cities” in October 2012 and “From Christmas lights to bio-energy: how technology will change our sense of place” in August 2012. The money-flows within those markets can be used as the basis of financing their infrastructure, as I discussed in “Digital Platforms for Smarter City Market-Making” in June 2012 and in several other articles described in “5. Put the financing in place” above.

(Lake Kutubu, Papua New Guinea, where Chevron’s oilfield operations were designed in collaboration with the local community. Photo by Iain Taylor)

Commentary: a new form of leadership

Andrew Zolli’s book “Resilience: why things bounce back” contains many examples of “smart” initiatives that have transformed systems such as emergency response, agriculture, fishing, finance and gang culture, most, but not all, of which are enabled by technology.

A common theme from all of them is productive co-operation and co-creation between large formal organisations (such as businesses and public sector institutions) and informal community groups or individuals (examples in Resilience include subsistence farmers, civic activitists and pacific island fishermen). Jared Diamond made similar observations about successful examples of socially and environmentally sustainable resource extraction businesses, such as Chevron’s sustainable operations in the Kutubu oilfield in Papua New Guinea, in his book “Collapse“.

Zolli identified a particular style of individual behaviour that was crucial in bringing about these collaborations that he called “translational leadership“: the ability to build new bridges; to bring together the resources of local communities and national and international institutions; to harness technology at appropriate cost for collective benefit; to step in and out of institutional and community behaviour and adapt to different cultures, conversations and approaches to business; and to create business models that balance financial health and sustainability with social and environmental outcomes.

That’s precisely the behaviour and leadership that I see in successful Smarter Cities initiatives. It’s sometimes shown by the leaders of public authorities, Universities or private businesses; but it’s equally often shown by community activists or entrepreneurs.

For me, this is one of the most exciting and optimistic insights about Smarter Cities: the leaders who catalyse their emergence can come from anywhere. And any one of us can choose to take a first step in the city where we live.