Why Smart Cities still aren’t working for us after 20 years. And how we can fix them.

February 1, 2016 37 Comments

(The futuristic “Emerald City” in the 1939 film “The Wizard of Oz“. The “wizard” who controls the city is a fraud who uses theatrical technology to disguise his lack of real power.)

(I was recently asked to give evidence to the United Nations Commission on Science and Technology for Development during the development of their report on Smart Cities and Infrastructure. This article is based on my presentation, which you can find here).

The idea of a “Smart City” (or town, or region, or community) is 20 years old now; but despite some high profile projects and a lot of attention, it has so far achieved relatively little.

The goal of a Smart City is to invest in technology in order to create economic, social and environmental improvements. That is an economic and political challenge, not a technology trend; and it is an imperative challenge because of the nature and extent of the risks we face as a society today. Whilst the demands created by urbanisation and growth in the global population threaten to outstrip the resources available to us, those resources are under threat from man-made climate change; and we live in a world in which many think that access to resources is becoming dangerously unfair.

Surely, then, there should be an urgent political debate concerning how city leaders and local authorities enact policies and other measures to steer investments in the most powerful tool we have ever created, digital technology, to address those threats?

In honesty, that debate is not really taking place. There are endless conferences and reports about Smart Cities, but very, very few of them tackle the issues of financing, investment and policy – they are more likely to describe the technology and engineering solutions behind schemes that appear to create new efficiencies and improvements in transport and energy systems, for example, but that in reality are unsustainable because they rely on one-off research and innovation grants.

Because Smart Cities are usually defined in these terms – by the role of technology in city systems rather than by the role of policy in shaping the outcomes of investment – the idea has not won widespread interest and support from the highest level of political leadership – the very people without whom the policy changes and investments that Smart Cities need will not be made.

And because Smart Cities are usually discussed as projects between technology providers, engineers, local authorities and universities, the ordinary people who vote for politicians, pay taxes, buy products, use public services and make businesses work are not even aware of the idea, let alone supportive of it.

(William Robinson Leigh’s 1908 painting “Visionary City” envisaged future cities constructed from mile-long buildings of hundreds of stories connected by gas-lit skyways for trams, pedestrians and horse-drawn carriages. A century later we’re starting to realise not only that developments in transport and power technology have eclipsed Leigh’s vision, but that we don’t want to live in cities constructed from buildings on this scale.)

The fact that the Smart Cities movement confuses itself with inconsistent and contradictory definitions exacerbates this lack of engagement, understanding and support. From the earliest days, it has been defined in terms of either smart infrastructure or smart citizens; but rarely both at the same time.

For example, in “City of Bits” in 1996, William Mitchell, Director of the Smart Cities Research Group at MIT’s Media Lab, predicted the widespread deployment of digital technology to transform city infrastructures:

“… as the infobahn takes over a widening range of functions, the roles of inhabited structures and transportation systems are shifting once again, fresh urban patterns are forming, and we have the opportunity to rethink received ideas of what buildings and cities are, how they can be made, and what they are really for.”

Whilst in their paper “E-Governance and Smart Communities: A Social Learning Challenge“, published in the Social Science Computer Review in 2001, Amanda Coe, Gilles Paquet and Jeffrey Roy described the 1997 emergence of the idea of “Smart Communities” in which citizens and communities are given a stronger voice in their own governance by the power of internet communication technologies:

“A smart community is defined as a geographical area ranging in size from a neighbourhood to a multi-county region within which citizens, organizations and governing institutions deploy and embrace NICT [“New Information and Communication Technologies”] to transform their region in significant and fundamental ways (Eger 1997). In an information age, smart communities are intended to promote job growth, economic development and improve quality of life within the community.”

Because few descriptions of a Smart City reflect both of those perspectives in harmony, many Smart City discussions quickly create arguments between opposing camps rather than constructive ideas: infrastructure versus people; top-down versus bottom-up; technology versus urban design; proprietary technology versus open source; public service improvements versus the enablement of open innovation – and so on.

I haven’t seen many political leaders or the people who vote for them be impressed by proposals whose advocates are arguing with each other.

The emperor has no wearable technology … why we’re not really investing in Smart Cities

The consequence of this lack of cohesion and focus is that very little real money is being invested in Smart Cities to create the outcomes that cities, towns, regions and whole countries have set out for themselves in thousands of Smart City visions and strategies. The vast majority of Smart City initiatives to date are pilot projects funded by research and innovation grants. There are very, very few sustainable, repeatable solutions yet.

There are three reasons for this; and they will have serious economic and social consequences if we don’t address them.

Firstly, the investment streams available to most of those who are trying to shape Smart Cities initiatives – engineers, technologists, academics, local authority officers and community activists – are largely limited to corporate research and development funds, national and international innovation programmes and charitable or socially-focussed grants. Those are important sources of funding, but they are only available at a scale sufficient to prove that good new ideas can work through individual, time-limited projects. They are not intended to fund the deployment of those ideas across cities everywhere, or to construct new infrastructure at city scale, and they are not remotely capable of doing so.

(United States GDP plotted against median household income from 1953 to present. Until about 1980, growth in the economy correlated to increases in household wealth. But from 1980 onwards as digital technology has transformed the economy, household income has remained flat despite continuing economic growth. From “The Second Machine Age“, by MIT economists Andy McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, summarised in this article.)

Secondly and conversely, the massive investments that are being made in smart technology at a scale that is transforming our world are primarily commercial: they are investing in technology to develop new products and services that consumers want to buy. That’s guaranteed to create convenience for consumers and profit for companies; but it’s far from guaranteed to create resilient, socially mobile, vibrant and healthy cities. It’s just as likely to reduce our life expectancy and social engagement by making it easier to order high-fat, high-sugar takeaway food on our smartphones to be delivered to our couches by drones whilst we immerse ourselves in multiplayer virtual reality games.

That’s why whilst technology advocates praise the ingenuity of technology-enabled “sharing economy” business models such as Airbnb and Uber, most other commentators point out that far from being platforms for “sharing” many are simply profit-seeking transaction brokers. More fundamentally, some economists are seriously concerned that the economy is becoming dominated by such platform business models and that the majority of the value they create is captured by a small number of platform owners – world leaders discussed these issues at the World Economic Forum’s Davos summit this year. There is real evidence that the exploitation of technology by business is contributing to the evolution of the global economy in a way that makes it less equal and that concentrates an even greater share of wealth amongst a smaller number of people.

Finally, the similarly massive investments continually made in property development and infrastructure in cities are, for the most part, not creating investments in digital technology in the public interest. Sometimes that’s because there’s no incentive to do so: development investors make their returns by selling the property they construct; they often have no interest in whether the tenants of that property start successful digital businesses, and they receive no income from any connectivity services those tenants might use. In other cases, policy actively inhibits more socially-minded developers from providing digital services. One developer of a £1billion regeneration project told me that European Union restrictions on state aid had prevented them making any investment in connectivity. They could only build buildings without connectivity – in an area with no mobile coverage – and attempt to attract people and businesses to move in, thereby creating demand for telecommunications companies to subsequently compete to fulfil.

We’ll only build Smart Cities when we shape the market for investing in technology for city services and infrastructure

In her seminal 1961 work “The Death and Life of Great American Cities“, Jane Jacobs wrote that “Private investment shapes cities, but social ideas (and laws) shape private investment. First comes the image of what we want, then the machinery is adapted to turn out that image.”

Cities, towns, regions and countries around the world have set out their self-images of a Smart future, but we have not adapted the financial, regulatory and economic machinery – the policies, the procurement practises, the development frameworks, the investment models – to incentivise the private sector to create them.

I do not mean to be critical of the private sector in this article. I have worked in the private sector for my entire career. It is the engine of our economy, and without its profits we would not create the jobs needed by a growing global population, or the means to pay the taxes that sustain our public services, or the surplus wealth that creates an ability to invest in our future.

But one of the fallacies of large parts of the Smart Cities movement, and of a significant part of the overall debate concerning the enormous growth in value of the technology economy, is the assumption that economic growth driven by private sector investments in technology to improve business performance will create broad social, economic and environmental benefits.

There is no guarantee that it will. Outside philanthropy, charitable donations and social business models, private sector investments are made in order to make a profit, period. In doing so, social, economic and environmental benefits may also be created, but they are side effects which, at best, result from the informed investment choices of conscientious business leaders. At worst, they are simply irrelevant to the imperative of the profit motive.

Some businesses have the scale, vision and stability to make more direct links in their strategies and decision-making to the dependency between their success as businesses and the health of the society in which they operate – Unilever is a notable and high profile example. And all businesses are run by real people whose consciences influence their business decisions (with unfortunate exceptions, of course).

But those examples do not in any way add up to the alignment of private sector investment objectives with the aspirations of city authorities or citizens for their future. And as MIT economists Andy McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, amongst others, have shown, most current evidence indicates that the technology economy is exacerbating the inequality that exists in our society (see graph above). That is the opposite of the future aspirations expressed by many cities, communities and their governments.

This leads us to the political and economic imperative represented by the Smart Cities movement: to adapt the machinery of our economy to influence investments in technology so that they contribute to the social, economic and environmental outcomes that we want.

A leadership imperative to learn from the past

Those actions can only be taken by political leaders; and they must be taken because without them developments and investments in new technology and infrastructure will not create ubiquitously beneficial outcomes. Historically, there is plenty of evidence that investments in technology and infrastructure can create great harm if market forces alone are left to shape them.

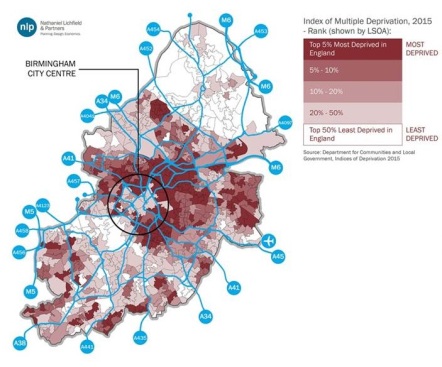

(Areas of relative wealth and deprivation in Birmingham as measured by the Indices of Multiple Deprivation. Birmingham, like many of the UK’s Core Cities, has a ring of persistently deprived areas immediately outside the city centre, co-located with the highest concentration of transport infrastructure allowing traffic to flow in and out of the centre)

For example, in the decades after the Second World War, cities in developed countries rebuilt themselves using the technologies of the time – concrete and the internal combustion engine. Networks of urban highways were built into city centres in the interests of connecting city economies with national and international transport links to commerce.

Those infrastructures supported economic growth; but they did not provide access to the communities they passed through.

The 2015 Indices of Multiple Deprivation in the UK demonstrate that some of those communities were greatly harmed as a result. The indices identify neighbourhoods with combinations of low levels of employment and income; poor health; poor access to quality education and training; high levels of crime; poor quality living environments and shortages of quality housing and services. An analysis of these areas in the UK’s Core Cities (the eight economically largest cities outside London, plus Glasgow and Cardiff) show that many of them exist in rings surrounding relatively thriving city centres. Whilst clearly the full causes are complex, it is no surprise that those rings feature a concentration of transport infrastructure passing through them, but primarily serving the interests of those passing in and out of the centre. (And this is without taking into account the full health impacts of transport-related pollution, which we’re only just starting to appreciate).

Similar effects can be seen historically. In their report “Cities Outlook 1901“, Centre for Cities explored the previous century of urban development in the UK, examining why at various times some cities thrived and some did not. They concluded that the single most important influence on the success of cities was their ability to provide their citizens with the right skills and opportunities to find employment, as the skills required in the economy changed as technology evolved. (See the sample graph below). A recent short article in The Economist magazine similarly argued that history shows there is no inevitable mechanism that ensures that the benefits of economic growth driven by technology-enabled productivity improvements are broadly distributed. It cites huge investments made in the US education system in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries to ensure that the general population was in a position to benefit from the technological developments of the Industrial Revolution as an example of the efforts that may need to be made.

Why smart cities are a political leadership challenge

So, to summarise the arguments I’ve made so far:

From global urbanisation and population growth to man-made climate change we are facing some of the most serious and acute challenges in our history, as well as the persistent challenge of inequality. But the most powerful tool that is shaping a transformation of our society and economy, digital technology, is, for the most part, not being used to address those challenges. The vast majority of investments in it are being made simply in the interests of profitable returns. Our political leaders are not shaping the markets in which those investment are made, or influencing public sector procurement practises, in order to create broader social, economic and environmental outcomes.

So what can we do about that?

We need to persuade political leaders to act – the leaders of cities; of local authorities more generally; and national politicians. I’m trying to do that using the arguments set out in this article, approaching “Smart Cities” not as a technology initiative but as a political and economic issue made urgent by imperative challenges to society.

I can imagine three arguments against that proposition, which I’d like to tackle first, before going on to talk about the actions that we need those leaders to take.

(Population changes in Blackburn, Burnley and Preston from 1901-2001. In the early part of the century, all three cities grew, supported by successful manufacturing economies. But in the latter half, only Preston continued to grow as it transitioned successfully to a service economy. If cities do not adapt to changes in the economy driven by technology, history shows that they fail. From “Cities Outlook 1901” by Centre for Cities)

The first argument is: why focus on cities? What about the rest of the world, and in particular the challenges of smaller towns, which are often overlooked; or rural regions, which are distinctive and deserve focus in their own right?

There are two replies to this argument. The first is that cities do represent the most sizeable challenge. Since 2010, more than half the world’s population has lived in urban areas, and that’s expected to rise to 70% by 2050. Cities drive the majority of the world’s economy, consume the majority of resources in the most concentrated way and create the majority of the pollution driving climate change. By focussing on cities we focus on most of our challenges at the same time, and in the places where they are most concentrated; and we focus on a unit of governance that is able to act decisively and with understanding of local context.

And that brings us to the second reply: most of the arguments I make in this article aren’t really about cities, they’re about the need for the leaders of local governments – cities, towns and regions – to take action. That applies to any local authority, not just to cities.

The second counter-argument is that my proposal is “top-down” and that instead we should focus on the “bottom-up” creativity that is the richest source of innovation and of practical solutions to problems that are rooted in local context.

My answer to this challenge is that I agree completely that it is bottom-up innovation that will create the majority of the answers to our challenges. But bottom-up innovation is already happening everywhere around us – it is what everyone does every day to create a better business, a better community, a better life. The problem with bottom-up innovation doesn’t lie in making it happen; it lies in enabling it to have a bigger impact. If bottom-up innovation on its own were the answer, then we wouldn’t have the staggering and increasing levels of inequality that we see today, and the economic growth created by the information revolution would be more broadly distributed.

Ultimately, it’s not the bottom-up innovators who need persuading to take action: they’re already acting. It’s the top-down leaders and policy-makers who are not doing what we need them to do: setting the policies that will influence investments in digital technology infrastructure to create better opportunities and support for citizen-led, community-led and business-led innovation. That’s why I’m focussing this article on those leaders and the actions we need them to take.

The third argument works similarly to the second argument, and it’s that we should be focussing on people, not on technology and policy.

Yes, of course we should be focussing on people: their creativity, the detail of their daily lives, and the outcomes that matter to them. But two central points to my argument are that digital technology is a new and revolutionary force reshaping our world, our society and our economy; and that the benefits of that revolution are not being equitably distributed. The main thing that’s not working for people right now is the impact of digital technology on society, and the main reason for that is the lack of action by political leaders. So that’s what we should concentrate on fixing.

Finally, I can summarise my response to all of those arguments in a simple statement: first we have to persuade political leaders to act, because many of them are not acting on these issues at the moment; and then we have to persuade them to act in the right way – to support bottom-up innovation through investment in open technology infrastructures and to put the interests of people at the heart of the policies that drive and shape that investment.

(Innovation Birmingham’s Chief Executive David Hardman describes the £7m “iCentrum” facility which will open in March 2016 to local stakeholders. It will offer entrepreneurial companies opportunities to co-develop smart city products and services with larger organisations such as RWE nPower, the Transport Systems Catapult and Centro, Birmingham’s Public Transport Executive)

Learning from what’s worked

This might all sound rather negative so far; and in a sense that’s intentional because I want to be very clear in my message that I do not think we are doing enough.

But I have a positive message too: if we can persuade our political leaders to act, then it’s increasingly clear what we need them to do. Whilst the majority of “Smart City” initiatives are unsustainable pilot and innovation projects, that’s not true of them all.

In the UK, from Sunderland to London to Newcastle to Birmingham there are examples of initiatives that are supported by sustainable funding sources and investment streams; that are not dependent on research and development grants from national or international innovation funds or technology companies; and that essentially could be applied by any city or community.

I summarised these repeatable models recently in the article “4 ways to get on with building Smart Cities. And the societal failure that stops us using them“:

1. Include Smart City criteria in the procurement of services by local authorities to encourage competitive innovation from private sector providers. Whilst local authority budgets are under pressure around the world, and have certainly suffered enormous cuts in the UK, local authorities nevertheless spend up to billions of pounds sterling annually on goods, services and staff time. The majority of procurements that direct that spending still procure traditional goods and services through traditional criteria and contracts. By contrast, Sunderland, a UK city, and Norfolk, a UK county, have shown that by emphasising city and regional aspirations in procurement scoring criteria it is possible to incentivise suppliers to invest in smart solutions that contribute to local objectives.

2. Encourage development opportunities to include “smart” infrastructure. Investors invest in infrastructure and property development because it creates returns for them – to the tune of billions of pounds sterling annually in the UK. Those investments are already made in the context of regulations – planning frameworks, building codes and energy performance criteria, for example. Those regulations can be adapted to demand that investments in property and physical infrastructure include investment in digital infrastructure in a way that contributes to local authority and community objectives. The East Wick and Sweetwater development in London – a multi-£100million development that is part of the 2012 Olympics legacy and that is financed by a pension fund investment – was awarded to it’s developer based in part on their commitments to invest in this way.

3. Commit to entrepreneurial programmes. There are many examples of new urban or public services being delivered by entrepreneurial organisations who develop new business and operating models enabled by technology – I’ve already cited Uber and Airbnb as examples that contribute to traveller convenience; Casserole Club, a service that uses social media to connect people who can’t provide their own food with neighbours who are happy to cook an extra portion of a meal for someone else, is an example that has more obviously social benefits. Many cities have local investment funds and support services for entrepreneurial businesses, and Sunderland’s Software Centre, Birmingham’s iCentrum development, Sheffield’s Smart Lab and London’s Cognicity accelerator are examples where those investments have been linked to local smart city objectives.

4. Enable and support Social Enterprise. The objectives of Smart Cities are analogous to the “triple bottom line” objectives of Social Enterprises – organisations whose finances are sustained by revenues from the products or services that they provide, but that commit themselves to social, environmental or economic outcomes, rather than to maximising their financial returns to shareholders. A vast number of Smart City initiatives are carried out by these organisations when they innovate using technology. Cities that find a way to systematically enable social enterprises to succeed could unlock a reservoir of beneficial innovation, as the Impact Hub network, a global community of collaborative workspaces, has shown.

How to lead a smart city: Commitment, Collaboration, Consistency and Community

Each of the approaches I’ve described is dependent on both political leadership from a local authority and collaboration with regional stakeholders – businesses, developers, Universities, community groups and so on.

So the first task for political leaders who wish to drive an effective Smart City programme is to facilitate the co-creation of regional consensus and an action plan (I’m not going to use the word “roadmap”. My experience of Smart Cities roadmaps is that they are, as the name implies, passive documents that don’t go anywhere).

I can sum up how to do that effectively using “four C’s”: Commitment, Collaboration, Consistency and Community:

Commitment: a successful approach to a Smart City or community needs the commitment, leadership and active engagement of the most senior local government leaders. Of course, elected Mayors, Council Leaders and Chief Executives are busy people with a multitude of responsibilities and they inevitably delegate; but this is a responsibility that cannot be delegated too far. The vast majority of local authorities that I have seen pursue this agenda with tangible results – through whichever approach, even those authorities who have been successful funding their initiatives through research and innovation grants – have appointed a dedicated Executive officer reporting directly to the Chief Executive and with a clear mandate to create, communicate and drive a collaborative smart strategy and programme.

Collaboration: a collaborative, empowered regional stakeholder forum is needed to convene local resources. Whilst a local authority is the only elected body with a mandate to set regional objectives, local authorities directly control only a fraction of regional resources, and do not directly set many local priorities. Most approaches to Smart Cities require coordinated activity by a variety of local organisations. That only comes about if those organisations decide to collaborate at the most senior level, mutually agree their objectives for doing so, and meet regularly to agree actions to achieve them. The local authority’s elected mandate usually makes it the most appropriate organisation to facilitate the formation and chair the proceedings of such fora; but it cannot direct them.

Consistency: in order to collaborate, regional stakeholders need to agree a clear, consistent, specific local vision for their future. Without that, they will lack a context in which to take decisions that reconcile their individual interests with shared regional objectives; and any bids for funding and investments they make, whether individually or jointly, will appear inconsistent and unconvincing.

Community: finally, the only people who really know what a smart city should look like are the citizens, taxpayers, voters, customers, business owners and employees who form its community; who will live and work in it; and who will ultimately pay for it through their taxes. It’s their bottom-up innovation that will give rise to the most meaningful and effective initiatives. Their voice – heard through events, consultation exercises, town hall meetings, social media and so on – should lead to the visions and policies to create an environment in which they can flourish.

(Birmingham’s newly opened city centre trams are an example of a reversal of 20th century trends that prioritised car traffic over the public transport systems that we have re-discovered to be so important to healthy cities)

Beyond “top-down” versus “bottom-up”: Translational Leadership and Smart Digital Urbanism

Having established that there’s a challenge worth facing, argued that we need political leaders to take action to address it, and explored what that action should be, I’d like finally to return to one of the arguments I explored along the way.

Action by political leaders is, almost by definition, “top-down”; and, whilst I stand by my argument that it’s the most important missing element of the majority of smart cities initiatives today, it’s vitally important that those top-down actions are taken in such a way as to encourage, enable and empower “bottom-up” innovation by the people, communities and businesses from which real cities are made.

It’s not only important that our leaders take the actions that I’ve argued for; it’s important that they act in the right way. Smart cities are not “business as usual”; and they are also not “behaviour as usual”.

The smart cities initiatives that I have been part of or had the privilege to observe, and that have delivered meaningful outcomes, have taken me on a personal journey. They have involved meeting with, listening to and working with people, organisations and communities that I would not have previously expected to be part of my working life, and that I was not previously familiar with in my personal life – from social enterprises to community groups to individual people with unusual ideas.

Writing in “Resilience: Why Things Bounce Back”, Andrew Zolli observes that the leaders of initiatives that have created real, lasting and surprising change in communities around the world show a quality that he defines as “Translational Leadership“. Translational leaders have the ability to overcome the institutional and cultural barriers to engagement and collaboration between small-scale, informal innovators in communities and large-scale, formal institutions with resources. This is precisely the ability that any leaders involved in smart cities need in order to properly understand how the powerful “top-down” forces within their influence – policies, procurements and investments – can be adapted to empower and enable real people, real communities and real businesses.

Translational leaders understand that their role is not to direct change, but to create the conditions in which others can be successful.

We can learn how to create those conditions from the decades of experience that town planners and urban designers have acquired in creating “human-scale cities” that don’t repeat the mistakes that were made in constructing vast urban highways, tower blocks and housing projects from unforgiving concrete in the past century.

And there is good precedent to do so. It is not just that the experience of town planners and urban designers leads us unmistakably to design thinking that focusses on the needs of the millions of individual citizens whose daily experiences collectively create the behaviour of cities. That is surely the only approach that will succeed; and the designers of smart city technologies and infrastructures will fail unless they take it. But there is also a long-lasting and profound relationship between the design techniques of town planners and of software engineers. The basic architectures of the internet and mobile applications we use today were designed using those techniques in the last decade of the last millennium and the first decade of this one.

The architect Kelvin Campbell’s concept of “massive/small smart urbanism” can teach us how to join the effects of “top-down” investments and policy with the capacity for “bottom-up” innovation that exists in people, businesses and communities everywhere. In the information age, we create the capacity for “massive amounts of small-scale innovation” if digital infrastructures are accessible and adaptable through the provision of open data interfaces, and accessible from open source software on cloud computing platforms – the digital equivalent of accessible public space and human-scale, mixed-used urban environments.

I call this “Smart Digital Urbanism”, and many of its principles are already apparent because their value has been demonstrated time and again. These principles should be the starting point for adapting planning frameworks, procurement practises and the other policies that influence spending and investment in cities and public services.

Re-stating what Smart Cities are all about

Defining and re-defining the “Smart City” is a hoary old business – as I pointed out at the start of this article, we’ve been at it for 20 years now, and without much success.

But definitions are important: saying what you mean to do is an important first step in acting successfully, particularly in a collaborative, public context.

So I’ll end this article by offering another attempt to sum up a smart city – or community – in a way that emphasises what I know from experience are the important factors that will lead to successful actions and outcomes, rather than the endless rounds of debate that we can’t allow to continue any longer:

A Smart City or community is one which successfully harnesses the most powerful tool of our age – digital technology – to create opportunities for its citizens; to address the most severe acute challenges the human race has ever faced, arising from global urbanisation and population growth and man-made climate change; and to address the persistent challenge of social and economic inequality. The policies and investments needed to do this demand the highest level of political leadership at a local level where regional challenges and resources are best understood, and particularly in cities where they are most concentrated. Those policies and investments will only be successful if they are enabling, not directing; if they result from the actions of leaders who are listening and responding to the people and communities they serve; and if they shape an urban environment and digital economy in which individual citizens, businesses and communities have the skills, opportunities and resources to create their own success on their own terms.

That’s not a snappy definition; but I hope it’s a useful definition that’s inclusive of the major issues and clearly points out the actions that are required by city, political, community and business leaders … and why it’s vitally important that we finally start taking them.

![(The sound artists FA-TECH [http://fa-tech.tumblr.com/] improvising in Shoreditch, London. Shoreditch's combination of urban character, cheap rents and proximity to London's business, financial centres and culture led to the emergence of a thriving technology startup community - although that community's success is now driving rents up, challenging some of the characteristics that enabled it.)](https://rickrobinson.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/6172318975_bcc84af6b2_o.jpg?w=431&h=320)