Intelligent Transport Systems need to get wiser … or transport will keep on killing us

November 2, 2015 3 Comments

(The 2nd Futurama exhibition at the 1964 New York World’s Fair displayed a vision for the future that in many ways reflected the concrete highways and highrises constructed at the time. We now recognise that the environments those structures created often failed to support healthy personal and community life. In 50 years’ time, how will we perceive today’s visions of Intelligent Transport Systems? Photo by James Vaughan)

Two weeks ago the Transport Systems Catapult published a “Traveller Needs and UK Capability Study”, which it called “the UK’s largest traveller experience study” – a survey of 10,000 people and their travelling needs and habits, complemented by interviews with 100 industry experts and companies. The survey identifies a variety of opportunities for UK innovators in academia and industry to exploit the predicted £56 billion market for intelligent mobility solutions in the UK by 2025, and £900 billion market worldwide. It is rightly optimistic that the UK can be a world leader in those markets.

This is a great example of the enormous value that the Catapult programme – inspired by Germany’s Fraunhofer Institutes – can play in transferring innovation and expertise out of University research and into the commercial economy, and in enabling the UK’s expert small businesses to reach opportunities in international markets.

But it’s also a great example of failing to connect the ideas of Intelligent Transport with their full impact on society.

I don’t think we should call any transport initiative “intelligent” unless it addresses both the full relationship between the physical mobility of people and goods with social mobility; and the significant social impact of transport infrastructure – which goes far beyond issues of congestion and pollution.

The new study not only fails to address these topics, it doesn’t mention them at all. In that light, such a significant report represents a failure to meet the Catapult’s own mission statement, which incorporates a focus on “wellbeing” – as quoted in the introduction to the report:

“We exist to drive UK global leadership in Intelligent Mobility, promoting sustained economic growth and wellbeing, through integrated, efficient and sustainable transport systems.” [My emphasis]

I’m surprised by this failing in the study as both the engineering consultancy Arup and the Future Cities Catapult – two organisations that have worked extensively to promote human-scale, walkable urban environments and human-centric technology – were involved in its production; as was at least one social scientist (although the experts consulted were otherwise predominantly from the engineering, transport and technology industries or associated research disciplines).

I note also that the list of reports reviewed for the study does not include a single work on urbanism. Jane Jacobs’ “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”, Jan Gehl’s “Cities for People“, Jeff Speck’s “Walkable City” and Charles Montgomery’s “The Happy City“, for example, all describe very well the way that transport infrastructures and traffic affect the communities in which most of the world’s population lives. That perspective is sorely lacking in this report.

Transport is a balance between life and death. Intelligent transport shouldn’t forget that.

These omissions matter greatly because they are not just lost areas of opportunity for the UK economy to develop solutions (although that’s certainly what they are). More importantly, transport systems that are designed without taking their full social impact into account have the most serious social consequences – they contribute directly to deprivation, economic stagnation, a lack of social mobility, poor health, premature deaths, injuries and fatalities.

As town planner Jeff Speck and urban consultant Charles Montgomery recently described at length in “Walkable City” and “The Happy City” respectively, the most vibrant, economically successful urban environments tend to be those where people are able to walk between their homes, places of work, shops, schools, local transport hubs and cultural amenities; and where they feel safe doing so.

But many people do not feel that it is safe to walk about the places in which they live, work and relax. Transport is not their only cause of concern; but it is certainly a significant one.

After motorcyclists (another group of travellers who are poorly represented), pedestrians and cyclists are by far the most likely travellers to be injured in accidents. According to the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents, for example, more than 60 child pedestrians are killed or injured every week in the UK – that’s over 3000 every year. No wonder that the number of children walking to school has progressively fallen as car ownership has risen, contributing (though it is obviously far from the sole cause) to rising levels of childhood obesity. In its 60 pages, the Traveller Needs study doesn’t mention the safety of pedestrians at all.

A recent working paper published by Transport for London found that the risk and severity of injury for different types of road users – pedestrians, cyclists, drivers, car passengers, bus passengers etc. – vary in complex and unexpected ways; and that in particular, the risks for each type of traveller vary very differently according to age, as our personal behaviours change, depending on the journeys we undertake, and according to the nature of the transport infrastructure we use.

These are not simple issues, they are deeply challenging. They are created by the tension between our need to travel in order to carry out social and economic interactions, and the physical nature of transport which takes up space and creates pollution and danger.

As a consequence, many of the most persistently deprived areas in cities are badly affected by large-scale transport infrastructure that has been primarily designed in the interests of the travellers who pass through them, and not in the interests of the people who live and work around them.

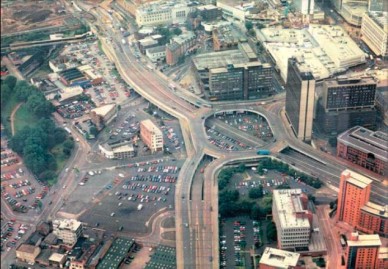

(Photo of Masshouse Circus, Birmingham, a concrete urban expressway that strangled the city centre before its redevelopment in 2003, by Birmingham City Council)

Birmingham’s Masshouse circus, for example, was constructed in the 1960s as part of the city’s inner ring-road, intended to improve connectivity to the national economy through the road network. However, the impact of the physical barrier that it created to pedestrian traffic can be seen by the stark difference in land value inside and outside the “concrete collar” that the ring-road created around the city centre. Inside the collar, land is valuable enough for tall office blocks to be constructed on it; whilst outside it is of such low value that it is used as a ground-level carpark. The reason for such a sharp change in value? People didn’t feel safe walking across or under the roundabout. The demolition of Masshouse Circus in 2002 enabled a revitalisation of the city centre that has continued for more than a decade.

Atlanta’s Buford Highway is a seven lane road which for two miles has no pavements, no junctions and no pedestrian crossings, passing through an area of houses, shops and businesses. It is an infrastructure fit only for vehicles, not for people. It allows no safe access along or across it for the communities it passes through – it is closed to them, unless they risk their lives.

In Sheffield, two primary schools were recently forced to close after measurements of pollution from diesel vehicles revealed levels 10-15 times higher than those considered the maximum safe limits, caused by traffic from the nearby M1 motorway. The vast majority of vehicles using the motorway comply to the appropriate emissions legislation depending on their age; and until specific emissions measurements were performed at the precise locations of the schools, the previous regional measurements of air quality had been within legal limits. This illustrates the failure of our transport policies to take into account the nature of the environments within which we live, and the detailed impact of transport on them. That’s why it’s now suspected that up to 60,000 people die prematurely every year in the UK due to the effects of diesel emissions, double previous estimates.

Nathaniel Lichfield and Partners recently published a survey of the 2015 Indices of Multiple Deprivation in the UK – the indices summarise many of the challenges that affect deprived communities such as low levels of employment and income; poor health; poor access to quality education and training; high levels of crime; poor quality living environments and shortages of quality housing and services.

Lichfield and Partners found that most of the UK’s Core Cities (the eight economically largest cities outside London, plus Glasgow and Cardiff) are characterised by a ring of persistently deprived areas surrounding their relatively thriving city centres. Whilst clearly the full causes are complex, it is no surprise that those rings feature a concentration of transport infrastructure passing through them, but primarily serving the interests of those passing in and out of the centre.

(Areas of relative wealth and deprivation in Birmingham as measured by the Indices of Multiple Deprivation. Birmingham, like many of the UK’s Core Cities, has a ring of persistently deprived areas immediately outside the city centre, co-located with the highest concentration of transport infrastructure allowing traffic to flow in and out of the centre)

These issues are not considered at all in the Transport Systems Catapult’s study. The word “walk” appears just three times in the document, all in a section describing the characteristics of only one type of traveller, the “dependent passenger” who does not own a car. Their walking habits are never examined, and walking as a transport choice is never mentioned or presented as an option in any of the sections of the report discussing challenges, opportunities, solutions or policy initiatives, beyond a passing mention that public transport users sometimes undertake the beginnings and ends of their journeys on foot. The word “pedestrian” does not appear at all. Cycling is mentioned only a handful of times; once in the same section on dependent passengers, and later on to note that “bike sharing [schemes have] not yet enjoyed high uptake in the UK”. The reason cited for this is that “it is likely that there are simply not enough use cases where using these types of services is convenient and cost-effective for travellers.”

If that is the case, why not investigate ways to extend the applicability of such schemes to broader use cases?

If only the sharing economy were a walking and cycling economy

The role of the Transport Systems Catapult is to promote the UK transport and transport technology industry, and this perhaps explains why so much of the study is focussed on public and private forms of powered transport and infrastructure. But there are many ways for businesses to profit by providing innovative technology and services that support walking and cycling.

What about way-finding services and street furniture that benefit pedestrians, for example, as the Future Cities Catapult recently explored? What about the cycling industry – including companies providing cargo-carrying bicycles as an alternative to small vans and trucks? What about the wearable technology industry to promote exercise measurement and pedestrian navigation along the safest, least polluted routes?

What about the construction of innovative infrastructure that promotes cycling and walking such as the “SkyCycle” proposal to build cycle highways above London’s railway lines, similar to the pedestrian and cycle roundabouts already built in Europe and China? What about the use of conveyor belts along similar routes to transport freight? What about the use of underground, pneumatically powered distribution networks for recycling and waste processing? All of these have been proposed or explored by UK businesses and universities.

And what about the UK’s world-class community of urban designers, town planners and landscape architects, some of whom are using increasingly sophisticated technologies to complement their professional skills in designing places and communities in which living, working and travelling co-exist in harmony? What about our world class University expertise researching visions for sustainable, liveable cities with less intrusive transport systems?

An even more powerful source of innovations to achieve a better balance between transportation and liveability could be the use of “sharing economy” business models to promote social and economic systems that emphasise local, human-powered travel.

Wikipedia describes the sharing economy as “economic and social systems that enable shared access to goods, services, data and talent“. Usually, these systems employ consumer technologies such as SmartPhones and social media to create online peer-to-peer trading networks that disrupt or replace traditional supply chains and customer channels – eBay is an obvious example for trading second hand goods, Airbnb connects travellers with people willing to rent out a spare room, and Uber connects passengers and drivers.

These business models can be enormously successful. Since its formation 8 years ago, Airbnb has acquired access to over 800,000 rooms to let in more than 190 countries; in 2014 the estimated value of this company which employed only 300 people at the time was $13 billion. Uber has demonstrated similarly astonishing growth.

However, it is much less clear what these businesses are contributing to society. In many cases their rapid growth is made possible by operating business models that side-step – or just ignore – the regulation that governs the traditional businesses that they compete with. Whilst they can offer employment opportunities to the providers in their trading networks, those opportunities are often informal and may not be protected by employment rights and minimum wage legislation. As privately held companies their only motivation is to return a profit to their owners.

By creating dramatic shifts in how transactions take place in the industries in which they operate, sharing economy businesses can create similarly dramatic shifts in transport patterns. For example, hotels in major cities frequently operate shuttle buses to transfer guests from nearby airports – a shared form of transport. Airbnb offer no such equivalent transfers to their independent accommodation. This is a general consequence of replacing large-scale, centrally managed systems of supply with thousands of independent transactions. At present there is very little research to understand these impacts, and certainly no policy to address them.

But what if incentives could be created to encourage the formation of sharing economy systems that promoted local transactions that can take place with less need for powered transport?

For example, Borroclub provides a service that matches someone who needs a tool with a neighbour who owns one that they could borrow. Casserole Club connects people who are unable to cook for themselves with a neighbours who are happy to cook and extra portion and share it. The West Midlands Collaborative Commerce Marketplace identifies opportunities for groups of local businesses to collaborate to win new contracts. Such “hyperlocal” schemes are not a new idea, and there are endless possibilities for them to reveal local opportunities to interact; but they struggle to compete for attention and investment against businesses purely focussed on maximising profits and investor returns.

Surely, a study that includes the Future Cities Catapult, Digital Catapult and Transport Systems Catapult amongst its contributors could have explored possibilies for encouraging and scaling hyperlocal sharing economy business models, alongside all those self-driving cars and multi-modal transport planners that industry seems to be quite willing to invest in on its own?

The study does mention some “sharing economy” businesses, including Uber; but it makes no mention of the controversy created because their profit-seeking focus takes no account of their social, economic and environmental impact.

It also mentions the role of online commerce in providing retail options that avoid the need to travel in person – and cites these as an option for reducing the overall demand for travel. But it fails to adequately explore the impact of the consequent requirements for delivery transport – other than to note the potential for detrimental impact on, let’s wait for it, not local communities but: local traffic!

“Enabling lifestyles is about more than just enabling and improving physical travel. 31% (19bn) of journeys made today would rather not have been made if alternative means were available (e.g. online shopping)” (page 15)

“Local authorities and road operators need to be aware that increased goods delivery can potentially have a negative impact on local traffic flows.” (page 24)

Why promote transactions that we carry out in isolation online rather than transactions that we carry out socially by walking, and that could contribute towards the revitalisation of local communities and town centres? Why mention “enabling lifestyles” without exploring the health benefits of walking, cycling and socialising?

(A poster from the International Sustainability Institute’s Commuter Toolkit, depicting the space 200 travellers occupy on Seattle’s 2nd Avenue when using different forms of transport, and intended to persuade travellers to adopt those forms that use less public space)

Self-driving cars as a consumer product represent selfish interests, not societal interests

The sharing economy is not the only example of a technology trend whose social and economic impact cannot be assumed to be positive. The same challenge applies very much to perhaps the most widely publicised transport innovation today, and one that features prominently in the new study: the self-driving car.

On Friday I attended a meeting of the UK’s Intelligent Transport Systems interest group, ITS-UK. Andy Graham of White Willow Consulting gave a report of the recent Intelligent Transport Systems World Congress in Bordeaux. The Expo organisers had provided a small fleet of self-driving cars to transfer delegates between hotels and conference venues.

Andy noted that the cars drove very much like humans did – and that they kept at least as large, if not a larger, gap between themselves and the car in front. On speaking to the various car manufacturers at the show, he learned that their market testing had revealed that car buyers would only be attracted to self-driving cars if they drove in this familiar way.

Andy pointed out that this could significantly negate one of the promoted advantages of self-driving cars: reducing congestion and increasing transport flow volumes by enabling cars to be driven in close convoys with each other. This focus on consumer motivations rather than the holistic impact of travel choices is repeated in the Transport Systems Catapults’ study’s consideration of self-driving cars.

Cars don’t only harm people, communities and the environment if they are diesel or petrol powered and emit pollution, or if they are involved in collisions: they do so simply because they are big and take up space.

Space – space that is safe for people to inhabit – is vital to city and community life. We use it to walk; to sit and relax; to exercise; for our children to play in; to meet each other. Self-driving cars and electric cars take up no less space than the cars we have driven for decades. Cars that are shared take up slightly less space per journey – but are nowhere near as efficient as walking, cycling or public transport in this regard. Car clubs might reduce the need for vehicles to be parked in cities, but they still take up as much space on the road.

The Transport Systems Catapult’s study does explore many means to encourage the use of shared or public transport rather than private cars; but it does so primarily in the interests of reducing congestion and pollution. The relationship between public space, wellbeing and transport is not explored; and neither is the – at best – neutral societal impact of self-driving cars, if their evolution is left to today’s market forces.

Just as the industry and politicians are failing to enact the policies and incentives that are needed to adapt the Smart Cities market to create better cities rather than simply creating efficiencies in service provision and infrastructure, the Intelligent Transport Systems community will fail to deliver transport that serves our society better if it doesn’t challenge our self-serving interests as consumers and travellers and consider the wider interests of society.

The Catapult’s report does highlight the potential need for city-wide and national policies to govern future transport systems consisting of connected and autonomous vehicles; but once again the emphasis is on optimising traffic flows and the traveller experience, not on optimising the outcomes for everyone affected by transport infrastructure and traffic.

As consumers we don’t always know best. In the words of one of the most famous transport innovators in history: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said ‘faster horses’.” (Henry Ford, inventor of the first mass-produced automobile, and of the manufacturing production line).

A failure that matters

The Transport Systems Catapult’s report doesn’t mention most of the issues I’ve explored in this article, and those that it does touch on are quickly passed over. In 60 pages it only mentions walking and cycling a handful of times; it never analyses the needs of pedestrians and cyclists, and beyond a passing mention of employers’ “cycle to work” schemes and the incorporation of bicycle hire schemes in multi-modal ticketing solutions, these modes of transport are never presented as solutions to our transport and social challenges.

This is a failure that matters. The Transport Systems Catapult is only one voice in the Intelligent Transport Systems community, and many of us would do well to broaden our understanding of the context and consequences of our work. For my part when I worked with IBM’s Intelligent Transport Systeams team several years ago I was similarly disengaged with these issues, and focussed on the narrower economic and technological aspects of the domain. It was only later in my career as I sought to properly understand the wider complexities of Smart Cities that I began to appreciate them.

But the Catapult Centre benefits from substantial public funding, is a high profile influencer across the transport sector, and is perceived to have the authority of a relatively independent voice between the public and private sectors. By not taking into account these issues, its recommendations and initiatives run the risk of creating great harm in cities in the UK, and anywhere else our transport industry exports its ideas to.

Both the “Smart Cities” and “Intelligent Transport” communities often talk in terms of breaking down silos in industry, in city systems and in thinking. But in reality we are not doing so. Too many Smart City discussions separate out “energy”, “mobility” and ”wellbeing” as separate topics. Too few invite town planners, urban designers or social scientists to participate. And this is an example of an “Intelligent Transport” discussion that makes the same mistakes.

(Pedestrian’s attempting to cross Atlanta’s notorious Buford Highway; a 7-lane road with no pavements and 2 miles between junctions and crossings. Photo by PBS)

In the wonderful “Walkable City“, Jeff Speck describe’s the epidemiologist Richard Jackson’s stark realisation of the life-and-death significance of good urban design related to transport infrastructure. Jackson was driving along the notorious two mile stretch of Atlanta’s seven lane Buford highway with no pavements or junctions:

“There, by the side of the road, in the ninety-five degree afternoon, he saw a woman in her seventies, struggling under the burden of two shopping bags. He tried to relate her plight to his own work as an epidemiologist. “If that poor woman had collapsed from heat stroke, we docs would have written the cause of death as heat stroke and not lack of trees and public transportation, poor urban form, and heat-island effects. If she had been killed by a truck going by the cause of death would have been “motor vehicle trauma”, and not lack of sidewalks and transit, poor urban planning and failed political leadership.”

We will only harness technology, transport and infrastructure to create better communities and better cities if we seek out and respect those cross-disciplinary insights that take seriously the needs of everyone in our society who is affected by them; not just the needs of those who are its primary users.

Our failure to do so over the last century is demonstrated by the UK’s disgracefully low social mobility; by those areas of multiple deprivation which in most cases have persisted for decades; and by the fact that as a consequence life expectancy for babies born today in the poorest parts of cities in the UK is 20 years shorter than for babies born today in the richest part of the same city.

That is the life and death impact of the transport strategies that we’ve had in the past; the transport strategies we publish today must do better.

Postscript 3rd November

The Transport Systems Catapult replied very positively on Twitter today to my rather forthright criticisms of their report. They said “Great piece Rick. The study is a first step in an ongoing discussion and we welcome further input/ideas feeding in as we go on.”

I’d like to think I’d respond in a similarly gracious way to anyone’s criticism of my own work!

What my article doesn’t say is that the Catapult’s report is impressively detailed and insightful in its coverage of those topics that it does include. I would absolutely welcome their expertise and resources being applied to a broader consideration of the topic of future transport, and look forward to seeing it.