From concrete to telepathy: how to build future cities as if people mattered

November 11, 2014 15 Comments

(An infographic depicting realtime data describing Dublin – the waiting time at road junctions; the location of buses; the number of free parking spaces and bicycles available to hire; and sentiments expressed about the city through social media)

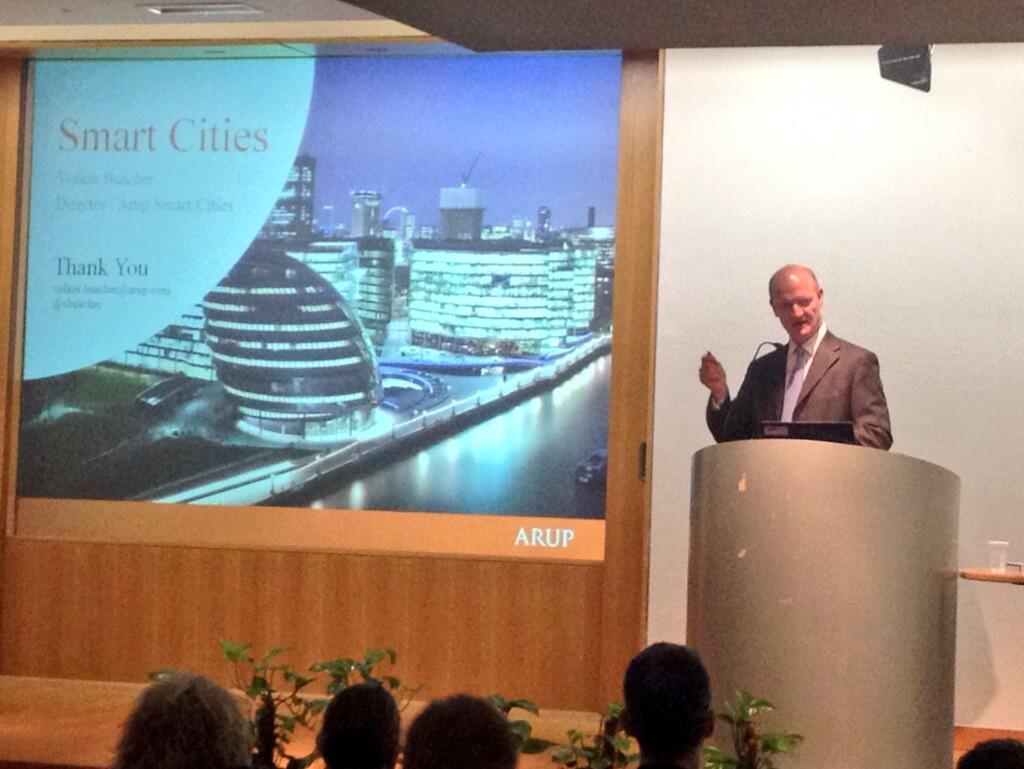

(I was honoured to be asked to speak at TEDxBrum in my home city of Birmingham this weekend. The theme of the event was “DIY” – “the method of building, modifying or repairing something without the aid of experts or professionals”. In other words, how Birmingham’s people, communities and businesses can make their home a better place. This is a rough transcript of my talk).

What might I, a middle-aged, white man paid by a multi-national corporation to be an expert in cities and technology, have to say to Europe’s youngest city, and one of its most ethnically and nationally diverse, about how it should re-create itself “without the aid of experts or professionals”?

Perhaps I could try to claim that I can offer the perspective of one of the world’s earliest “digital natives”. In 1980, at the age of ten, my father bought me one of the world’s first personal computers, a Tandy TRS 80, and taught me how to programme it using “machine code“.

But about two years ago, whilst walking through London to give a talk at a networking event, I was reminded of just how much the world has changed since my childhood.

I found myself walking along Wardour St. in Soho, just off Oxford St., and past a small alley called St. Anne’s Court which brought back tremendous memories for me. In the 1980s I spent all of the money I earned washing pots in a local restaurant in Winchester to travel by train to London every weekend and visit a small shop in a basement in St. Anne’s Court.

I’ve told this story in conference speeches a few times now, perhaps to a total audience of a couple of thousand people. Only once has someone been able to answer the question:

“What was the significance of St. Anne’s Court to the music scene in the UK in the 1980s?”

Here’s the answer:

Shades Records, the shop in the basement, was the only place in the UK that sold the most extreme (and inventive) forms of “thrash metal” and “death metal“, which at the time were emerging from the ashes of punk and the “New Wave of British Heavy Metal” in the late 1970s.

(Programming my Tandy TRS 80 in Z80 machine code nearly 35 years ago)

The process by which bands like VOIVOD, Coroner and Celtic Frost – who at the time were three 17-year-olds who practised in an old military bunker outside Zurich – managed to connect – without the internet – to the very few people around the world like me who were willing to pay money for their music feels like ancient history now. It was a world of hand-printed “fanzines”, and demo tapes painstakingly copied one at a time, ordered by mail from classified adverts in magazines like Kerrang!

Our world has been utterly transformed in the relatively short time between then and now by the phenomenal ease with which we can exchange information through the internet and social media.

The real digital natives, though, are not even those people who grew up with the internet and social media as part of their everyday world (though those people are surely about to change the world as they enter employment).

They are the very young children like my 6-year-old son, who taught himself at the age of two to use an iPad to access the information that interested him (admittedly, in the form of Thomas the Tank Engine stories on YouTube) before anyone else taught him to read or write, and who can now use programming tools like MIT’s Scratch to control computers vastly more powerful than the one I used as a child.

Their expectations of the world, and of cities like Birmingham, will be like no-one who has ever lived before.

And their ability to use technology will be matched by the phenomenal variety of data available to them to manipulate. As everything from our cars to our boilers to our fridges to our clothing is integrated with connected, digital technology, the “Internet of Things“, in which everything is connected to the internet, is emerging. As a consequence our world, and our cities, are full of data.

(The programme I helped my 6-year old son write using MIT’s “Scratch” language to cause a cartoon cat to draw a picture of a house)

My friend the architect Tim Stonor calls the images that we are now able to create, such as the one at the start of this article, “data porn”. The image shows data about Dublin from the Dublinked information sharing partnership: the waiting time at road junctions; the location of buses; the number of free parking spaces and bicycles available to hire; and sentiments expressed about the city through social media.

Tim’s point is that we should concentrate not on creating pretty visualisations; but on the difference we can make to cities by using this data. Through Open Data portals, social media applications, and in many other ways, it unlocks secrets about cities and communities:

- Who are the 17 year-olds creating today’s most weird and experimental music? (Probably by collaborating digitally from three different bedroom studios on three different continents)

- Where is the healthiest walking route to school?

- Is there a local company nearby selling wonderful, oven-ready curries made from local recipes and fresh ingredients?

- If I set off for work now, will a traffic jam develop to block my way before I get there?

From Dublin to Montpellier to Madrid and around the world my colleagues are helping cities to build 21st-Century infrastructures that harness this data. As technology advances, every road, electricity substation, University building, and supermarket supply chain will exploit it. The business case is easy: we can use data to find ways to operate city services, supply chains and infrastructure more efficiently, and in a way that’s less wasteful of resources and more resilient in the face of a changing climate.

Top-down thinking is not enough

But to what extent will this enormous investment in technology help the people who live and work in cities, and those who visit them, to benefit from the Information Economy that digital technology and data is creating?

This is a vital question. The ability of digital technology to optimise and automate tasks that were once carried out by people is removing jobs that we have relied on for decades. In order for our society to be based upon a fair and productive economy, we all need to be able to benefit from the new opportunities to work and be successful that are being created by digital technology.

(Photo of Masshouse Circus, Birmingham, a concrete urban expressway that strangled the city centre before its redevelopment in 2003, by Birmingham City Council)

Too often in the last century, we got this wrong. We used the technologies of the age – concrete, lifts, industrial machinery and cars – to build infrastructures and industries that supported our mass needs for housing, transport, employment and goods; but that literally cut through and isolated the communities that create urban life.

If we make the same mistake by thinking only about digital technology in terms of its ability to create efficiencies, then as citizens, as communities, as small businesses we won’t fully benefit from it.

In contrast, one of the authors of Birmingham’s Big City Plan, the architect Kelvin Campbell, created the concept of “massive / small“. He asked: what are the characteristics of public policy and city infrastructure that create open, adaptable cities for everyone and that thereby give rise to “massive” amounts of “small-scale” innovation?

In order to build 21st Century cities that provide the benefits of digital technology to everyone we need to find the design principles that enable the same “massive / small” innovation to emerge in the Information Economy, in order that we can all use the simple, often free, tools available to us to create our own opportunities.

There are examples we can learn from. Almere in Holland use analytics technology to plan and predict the future development of the city; but they also engage in dialogue with their citizens about the future the city wants. Montpellier in France use digital data to measure the performance of public services; but they also engage online with their citizens in a dialogue about those services and the outcomes they are trying to achieve. The Dutch Water Authority are implementing technology to monitor, automate and optimise an infrastructure on which many cities depend; but making much of the data openly available to communities, businesses, researchers and innovators to explore.

There are many issues of policy, culture, design and technology that we need to get right for this to happen, but the main objectives are clear:

- The data from city services should be made available as Open Data and through published “Application Programming Interfaces” (APIs) so that everybody knows how they work; and can adapt them to their own individual needs.

- The data and APIs should be made available in the form of Open Standards so that everybody can understand it; and so that the systems that we rely on can work together.

- The data and APIs should be available to developers working on Cloud Computing platforms with Open Source software so that anyone with a great idea for a new service to offer to people or businesses can get started for free.

- The technology systems that support the services and infrastructures we rely on should be based on Open Architectures, so that we have freedom to chose which technologies we use, and to change our minds.

- Governments, institutions, businesses and communities should participate in an open dialogue, informed by data and enlightened by empathy, about the places we live and work in.

If local authorities and national government create planning policies, procurement practises and legislation that require that public infrastructure, property development and city services provide this openness and accessibility, then the money spent on city infrastructure and services will create cities that are open and adaptable to everyone in a digital age.

Bottom-up innovation is not enough, either

(Coders at work at the Birmingham “Smart Hack”, photographed by Sebastian Lenton)

Not everyone has access to the technology and skills to use this data, of course. But some of the people who do will create the services that others need.

I took part in my first “hackathon” in Birmingham two years ago. A group of people spent a weekend together in 2012 asking themselves: in what way should Birmingham be better? And what can we do about it? Over two days, they wrote an app, “Second Helping”, that connected information about leftover food in the professional kitchens of restaurants and catering services, to soup kitchens that give food to people who don’t have enough.

Second Helping was a great idea; but how do you turn a great idea and an app into a change in the way that food is used in a city?

Hackathons and “civic apps” are great examples of the “bottom-up” creativity that all of us use to create value – innovating with the resources around us to make a better life, run a better business, or live in a stronger community. But “bottom-up” on it’s own isn’t enough.

The result of “bottom-up” innovation at the moment is that life expectancy in the poorest parts of Birmingham is more than 10 years shorter than it is in the richest parts. In London and Glasgow, it’s more than 20 years shorter.

If you’re born in the wrong place, you’re likely to die 10 years younger than someone else born in a different part of the same city. This shocking situation arises from many, complex issues; but one conclusion that it is easy to draw is that the opportunity to innovate successfully is not the same for everyone.

So how do we increase everybody’s chances of success? We need to create the policies, institutions, culture and behaviours that join up the top-down thinking that tends to control the allocation of resources and investment, especially for infrastructure, with the needs of bottom-up innovators everywhere.

Translational co-operation

(The Harborne Food School, which will open in the New Year to offer training and events in local and sustainable food)

The Economist magazine reminded us of the importance of those questions in a recent article describing the enormous investments made in public institutions such as schools, libraries and infrastructure in the past in order to distribute the benefits of the Industrial Revolution to society at large rather than concentrate them on behalf of business owners and the professional classes.

But the institutions of the past, such as the schools which to a large degree educated the population for repetitive careers in labour-intensive factories, won’t work for us today. Our world is more complicated and requires a greater degree of localised creativity to be successful. We need institutions that are able to engage with and understand individuals; and that make their resources openly available so that each of us can use them in the way that makes most sense to us. Some public services are starting to respond to this challenge, through the “Open Public Services” agenda; and the provision of Open Data and APIs by public services and infrastructure are part of the response too.

But as Andrew Zolli describes in “Resilience: why things bounce back“, there are both institutional and cultural barriers to engagement and collaboration between city institutions and localised innovation. Zolli describes the change-makers who overcome those barriers as “translational leaders” – people with the ability to engage with both small-scale, informal innovation in communities and large-scale, formal institutions with resources.

We’re trying to apply that “translational” thinking in Birmingham through the Smart City Alliance, a collaboration between 20 city institutions, businesses and innovators. The idea is to enable conversations about challenges and opportunities in the city, between people, communities, innovators and the organisations who have resources, from the City Council and public institutions to businesses, entrepreneurs and social enterprises. We try to put people and organisations with challenges or good ideas in touch with other people or organisations with the ability to help them.

This is how we join the “top-down” resources, policies and programmes of city institutions and big companies with the “bottom-up” innovation that creates value in local situations. A lot of the time it’s about listening to people we wouldn’t normally meet.

Partly as a consequence, we’ve continued to explore the ideas about local food that were first raised at the hackathon. Two years later, the Harborne Food School is close to opening as a social enterprise in a redeveloped building on Harborne High Street that had fallen out of use.

The school will be teaching courses that help caterers provide food from sustainable sources, that teach people how to set up and run food businesses, and that help people to adopt diets that prevent or help to manage conditions such as diabetes. The idea has changed since the “Second Helping” app was written, of course; but the spirit of innovation and local value is the same.

Cities that work like magic

(Images captured by MRI scan by Shinji Nishimoto, Alex G. Huth, An Vu and Jack L. Gallant, UC Berkley, 2011)

So what does all this have to do with telepathy?

The innovations and changes caused by the internet over the last two decades have accelerated as it has made information easier and easier to access and exchange through the advent of technologies such as broadband, mobile devices and social media. But the usefulness of all of those technologies is limited by the tools required to control them – keyboards, mice and touchscreens.

Before long, we won’t need those tools at all.

Three years ago, scientists at the University of Berkely used computers attached to an MRI scanner to recreate moving images from the magnetic field created by the brain of a person inside the scanner watching a film on a pair of goggles. And last year, scientists at the University of Washington used similar technology to allow one of them to move the other’s arm simply by thinking about it. A less sensitive mind-reading technology is already available as a headset from Emotiv, which my colleagues in IBM’s Emerging Technologies team have used to help a paralysed person communicate by thinking directional instructions to a computer.

Telepathy is now technology, and this is just one example of the way that the boundary between our minds, bodies and digital information will disappear over the next decade. As a consequence, our cities and lives will change in ways we’ve never imagined, and some of those changes will happen surprisingly quickly.

I can’t predict what Birmingham will or should be like in the future. As a citizen, I’ll be one of the million or so people who decide that future through our choices and actions. But I can say that the technologies available to us today are the most incredible DIY tools for creating that future that we’ve ever had access to. And relatively quickly technologies like bio-technology, 3D printing and brain/computer interfaces will put even more power in our hands.

As a parent, I get engaged in my son’s exploration of these technologies and help him be digitally aware, creative and responsible. Whenever I can, I help schools, Universities, small businesses or community initiatives to use them, because I might be helping one of IBM’s best future employees or business partners; or just because they’re exciting and worth helping. And as an employee, I try to help my company take decisions that are good for our long term business because they are good for the society that the business operates in.

We can take for granted that all of us, whatever we do, will encounter more and more incredible technologies as time passes. By remembering these very simple things, and remembering them in the hundreds of choices I make every day, I hope that I’ll be using them to play my part in building a better Birmingham, and better cities and communities everywhere.

(Shades Records in St. Anne’s Court in the 1980s. You can read about the role it played in the development of the UK’s music culture – and in the lives of its customers – in this article from Thrash Hits; or this one from Every Record Tells a Story. And if you really want to find out what it was all about, try watching Celtic Frost or VOIVOD in the 1980s!)